Photo Source: The Michigan State Capitol: A National Historic Landmark

IN THIS HIGH-STAKES ELECTION YEAR, voters are juggling a number of proposals, policies, and issues as they prepare to head to the polls. With so many topics to follow and news breaking every day, it’s no surprise that some politicians and political interest groups are actively trying to game the system.

This five-part series is about a quirk in our state government that lets them do that. This quirk has been used for more than 100 years, and despite the fact that it began as a way to let Michiganders have a say in our laws, it’s become into a pathway for politicians and special interest groups to slip past voters.

This year, it’s being used to put more power and more money into the hands of the wealthy.

We’re not flashing it in bright lights across your screen, demanding that you act now lest you lose your liberty. Instead, we’re dropping a multi-week investigation by our team into two explainers, and two rabbit holes – which you can read, share, and ask questions about as you decide which candidates and policies deserve your vote at the Nov. 8 general election.

At the center of this series is the idea of a loophole.

PART 1: THE LOOPHOLE

Just like any legislator can introduce a bill, Michigan citizens also have the right to propose new laws. Such a proposal is called a citizen initiative.

For a legislator to pass a law, they must convince a majority of their fellow legislators to vote for it. Then, the governor can either sign the law or veto it.

For citizens to pass an initiative, they must get a majority of their fellow citizens to vote for it. To do that, they first ask people to sign petitions. If a petition gets enough signatures in a certain timeframe, it becomes a ballot measure. A ballot measure is a law, issue, or question which goes on a ballot for voters to decide.

If more than 50% of people vote for the ballot measure, it becomes law 10 days later. That new law cannot be vetoed by the governor. This small detail offers the registered voters of Michigan more collective power than the Legislature.

Here’s where things start to get a little weird—but not yet deceptive. We’ll get to that.

Michigan is one of only nine states with a citizen initiative process that can become “indirect.” An indirect initiative essentially means that once a petition has enough signatures to become a ballot measure, lawmakers can choose to intercept it and pass it into law before it gets to the ballot.

Why would they do that?

- To go around the citizens. If lawmakers believe a majority of citizens will vote against an initiative they favor, they can simply pass it themselves and prevent it from appearing on the ballot.

- For more control over the initiative. When citizens vote to pass an initiative and it becomes law, any changes legislators want to make to it over time would require a three-fourths majority vote. However, if legislators indirectly pass the initiative, they can change the new law in their next session with a simple majority. (You’ll hear more about a recent example of this later.)

- To go around the governor. When a legislator proposes a law and a majority of their legislative colleagues vote to pass it, the governor has 14 days to veto the bill. With an indirect initiative, the governor does not have veto power—creating a potentially dangerous combination of big-money special interests and partisan legislative control.

HERE’S A QUICK, HYPOTHETICAL EXAMPLE OF HOW THIS COULD PLAY OUT:

Michigan dentists want to make more money, so they lobby their lawmakers for a new state law that forces all Michiganders to eat candy – which would inevitably result in more cavities across the state. Fueled by campaign donations from the sugar industry, lawmakers attempt to pass the plan into law.

The governor, who understands that forcing people to eat candy is a terrible idea, vetoes the legislation. Lawmakers are unable to override the veto, and the fledgling legislation dies.

Then, sugar industry lobbyists decide to throw a few million dollars at a new ballot initiative drive, called MI Sweet State, that would bring the new candy requirements to voters on the next election ballot. They hire hundreds of paid signature gatherers, specifically to target hungry people with a sweet tooth, and a marketing strategy firm to sugarcoat the dangers of excessive candy consumption.

Doctors are up in arms over the concept. Teachers rail against the impact so much sugar would have on learning. Even polling shows that most people don’t want to be forced to eat candy every day.

But with only 340,047 signatures standing in the way of veto-proof legislation, and with so many signature-gatherers— paid per signature—circulating the state, it’s not hard to get their petitions filed and submitted on time.

Knowing the issue might not pass the popular vote, sugar-industry backed lawmakers watch for MI Sweet State’s ballot initiative to come in. When it does, they step in and pass the law before Election Day.

Since MI Sweet State had enough signatures to become an initiative, it doesn’t matter what the governor or registered voters think. The lawmakers can indirectly pass it. Dentists everywhere rejoice.

Since 1963, when Michigan’s current Constitution was ratified, there have been 11 instances of the Legislature approving ballot initiatives proposed by the citizens before they could get on the ballot. Nearly all were taken up by Republican-majority state Legislatures. Four of those 11 were to restrict abortion rights.

Most recently, the indirect initiative process was used to remove Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s health emergency powers during the COVID-19 pandemic. That effort, known as Unlock Michigan, was a citizen initiative in 2020 and was indirectly passed by the Republican-majority Legislature before it could reach the ballot.

At this point, you might be wondering if this indirect initiative process is entirely above-board. It is. That is to say, it’s legal. Is it democratic? Well, non-partisan experts have their doubts, and have made recommendations to improve the system. However, Legislators haven’t always seen eye-to-eye on the need for reform.

Why?

That’s Part 2.

Politics

Michigan lawmakers look to break (another) state funding record for public schools

Democratic lawmakers are hashing out plans to bring state funding for Michigan’s public schools to another new, all-time high—and ensure teachers...

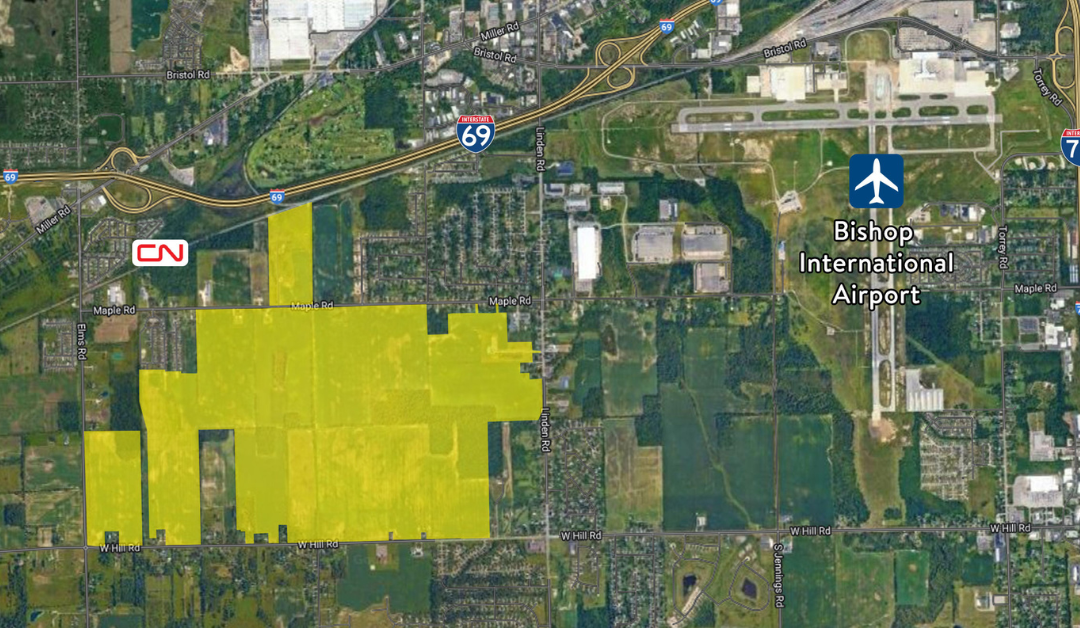

Mundy Twp. project gets state funding in effort to boost local manufacturing

More than $9 million awarded to a planned development project in Genesee County could provide a big boost to the local economy and help create...

It’s official: Your boss has to give you time off to recover from childbirth or get an abortion

Originally published by The 19th In what could be a groundbreaking shift in American workplaces, most employees across the country will now have...

Local News

More Michigan teens could soon take driver’s ed in their own schools

Privatization of driver’s education means that only 38 Michigan high schools offer affordable in-school driving classes for students. New grants...

That one time in Michigan: When we became the Wolverine State

How did Michigan become tied to an animal that's practically nonexistent there? Among the many nicknames that the state of Michigan has, arguably...