The Hispanic Festival in Grand Rapids is a celebration of West Michigan's Hispanic heritage. (Photo via Hispanic Center of West Michigan)

MICHIGAN—National Hispanic Heritage Month celebrates the contributions of Americans with lineage from Spanish-speaking countries. And Michigan definitely owes some of its culture to those of Hispanic descent. Four communities, in particular, stand out from the rest.

Mexicantown in Detroit

Originally known as “La Bagley,” Detroit’s Mexicantown is in southwest Detroit, with general boundary lines of Michigan Avenue, W. First Street, Livernois Avenue, and Rosa Parks Boulevard. Mexican families first came to Detroit in the early 1920s, escaping the Revolution of 1910 and the scarce opportunities in Mexico in favor of a booming industrial economy.

Many of Mexicantown’s residents came to Michigan from Los Altos, in the Mexican state of Jalisco. Los Altos has a string of villages that gave birth to some of Mexico’s most iconic cultural touchstones, including tequila, mariachi music, and cowboys. As these residents moved hundreds of miles from their homes, they looked for ways to make Mexicantown feel a bit more familiar—with authentic food, entertainment, and religious buildings reminiscent of life back in Mexico.

A century later, Mexicantown has endured as a diverse commercial corridor. In fact, the area is estimated to house more restaurants per square mile than anywhere else in the city.

Sunnyside in Adrian

The Continental Sugar Company in Blissfield started recruiting Mexican laborers for their sugar beet harvests in the 1920s. The result: A community rooted in Hispanic culture in the nearby city of Adrian.

When the Great Depression hit, those who immigrated to work for Continental didn’t have the money to return to Mexico at the end of the harvest season. Bolstered by rent-free incentives from the company, many of these migrant workers decided to stay through the year.

By World War II, sugar production took a backseat to wartime defense manufacturing—and many of those migrant workers took on key jobs in the new industry. With those jobs, it became clear that a more more permanent housing solution was needed. That’s when Sunnyside was born.

Facing significant racism, especially from Adrian landowners who didn’t want the workers to live in the city, the workers started their own little neighborhood outside the city. They called it Sunnyside, and there they opened a taqueria, a bakery, and other Mexican goods stores.

By 1950, half of the residents in Sunnyside were estimated to be of Hispanic heritage. After the Bracero Program—which granted temporary work permits for Mexican laborers—ended in the 1960s, Hispanic people sought better working and living conditions. By the 1970s, labor movement icon Cesar Chavez had taken note, and began visiting Adrian. When a nearby factory leak forced local agencies to deal with the leak’s pollution in the area, Sunnyside was officially connected to the city of Adrian’s water supply—a seemingly small change that led to better living conditions by Sunnyside’s residents.

Today, largely thanks to Sunnyside, about one in five Adrian residents are Hispanic.

Holland

Most Michiganders know Holland for its long-reaching Dutch roots. Less known is how important Mexican Americans are to its history.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Holland was an epicenter for sugar beet production, and with that industry came migrant workers from all over the world. European immigrants found quick economic upward mobility working the sugar beet farms, but the Immigration Act of 1917 heavily restricted European immigration. As a result, Hispanic immigrants began flocking to Holland in droves—a trend that has remained relatively steady over the last century.

When the Bracero Program was signed in 1942, many Hispanic immigrants went to work at places such as the Heinz pickle-manufacturing facility. But for those workers who were uneducated, some local farm owners eschewed the agreements of the Bracero Program, taking advantage of—and silencing—the migrant workers.

Advocacy groups formed to combat this discrimination, banding together in 1971 as Latin American United for Progress. LAUP was crucial in getting the Holland Chamber of Commerce to recognize the local Hispanic community, and to keep their history alive.

Within a few years, with the nationwide inspiration of Cesar Chavez, the more-empowered Hispanic people of the area picketed Meijer grocery stores to support the United Farm Workers Union and boycott foods not certified by the union. Though discrimination and prejudice continued to run rampant, the Hispanic community of Holland never faltered. Slowly, with enough resistance, multiple programs, organizations, and events emerged to recognize and support Hispanic people.

The Latin American United for Progress Fiesta, held annually in Holland, is a reminder of this story.

Old Town in Lansing

The Michigan Sugar Co. beet factory employed many Mexican immigrants in the 1920s—which also brought these workers and their families to the city of Lansing.

From the ’50s until the ’70s in Lansing’s Old Town, Latinx-owned businesses boomed. By 1974, there were so many Spanish-speaking people that it had its own Spanish newspaper.

Today, however, many of those buildings have closed down. Some long-term residents believe the Latinx community became divided when the original Cristo Rey Church was demolished in 1965 to make way for I-496. Though the church has since reopened, its new location continues to divide the community.

Even though the Old Town neighborhood has changed a lot over the last century, it’s still home to Lansing’s greatest concentration of Latinx residents. The main strip, Grand River Avenue, was even renamed “Cesar E. Chavez Avenue” in honor of the late labor leader.

Politics

Michigan lawmakers look to break (another) state funding record for public schools

Democratic lawmakers are hashing out plans to bring state funding for Michigan’s public schools to another new, all-time high—and ensure teachers...

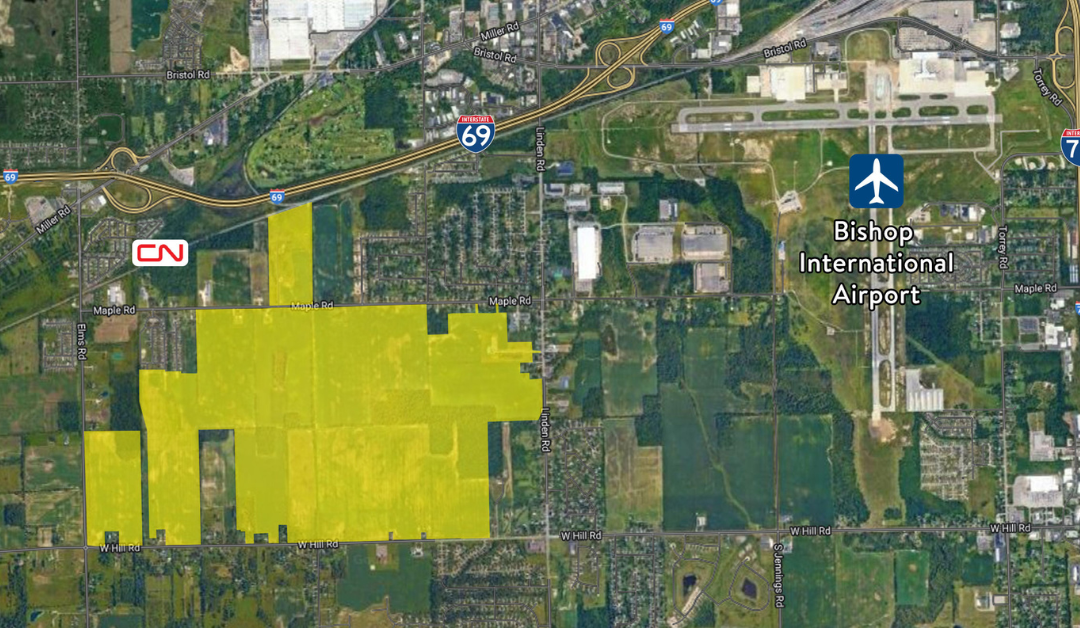

Mundy Twp. project gets state funding in effort to boost local manufacturing

More than $9 million awarded to a planned development project in Genesee County could provide a big boost to the local economy and help create...

It’s official: Your boss has to give you time off to recover from childbirth or get an abortion

Originally published by The 19th In what could be a groundbreaking shift in American workplaces, most employees across the country will now have...

Local News

That one time in Michigan: When we became the Wolverine State

How did Michigan become tied to an animal that's practically nonexistent there? Among the many nicknames that the state of Michigan has, arguably...

Readers’ Choice: Top 5 Bowling Spots in Michigan

From retro lanes — including one of the oldest running bowling alleys in the country — to modern entertainment centers, there's something for...