AP Photo/Rick Bowmer, File

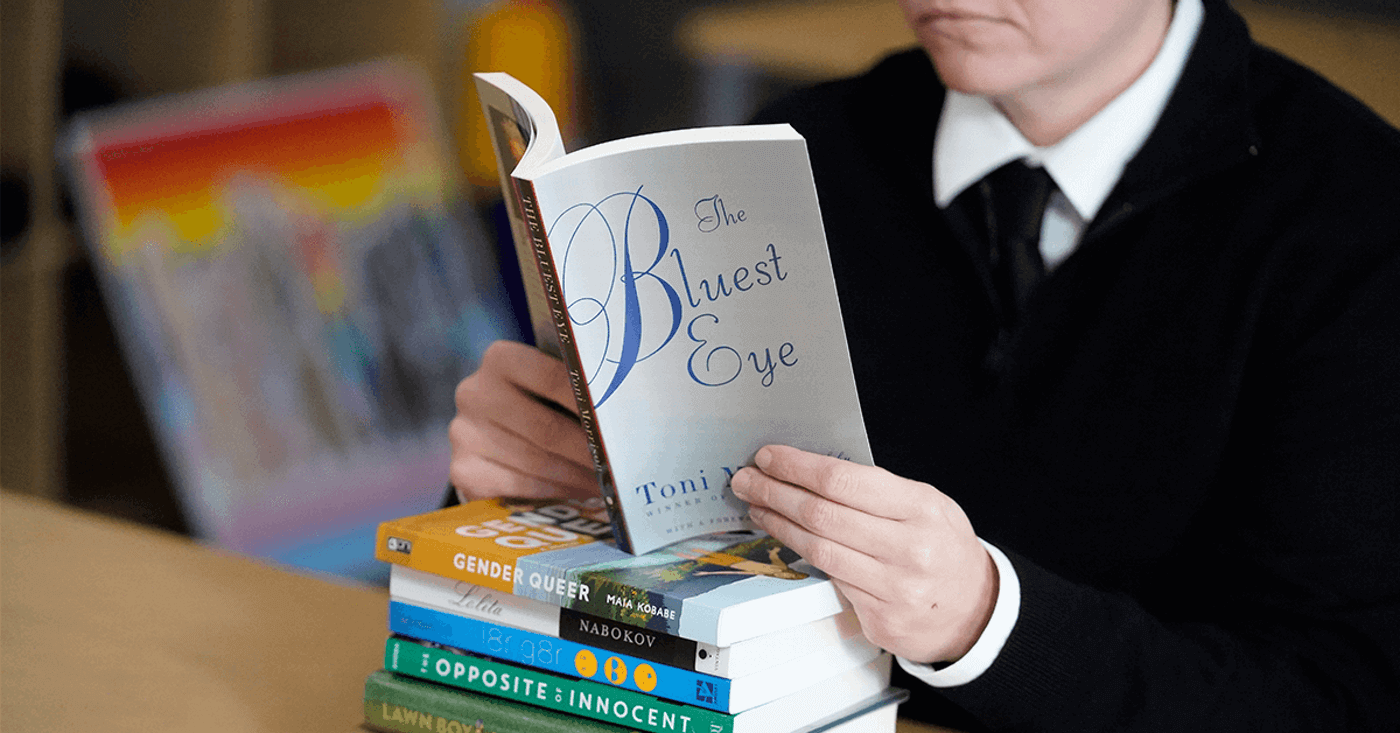

Michigan Republicans want to pass bills schools from teaching material that could be considered “anti-American” or “racist,” including the 1619 Project, a collection of essays on slavery, race, and the origins of America. Nearly four in five Michiganders oppose such efforts and believe it’s censorship.

Need to Know

- Seventy-nine percent of Michigan voters said they strongly or somewhat opposed lawmakers banning books in schools, while only 21% support such bans

- Some conservatives have stoked panic among parents that children are being taught “Critical Race Theory” and exploited those fears to ban books and censor how educators can teach about race and American history.

- In Michigan, Republicans introduced bills to ban schools from teaching anything about “critical race theory,” material from the New York Times’ 1619 Project on the origins of slavery, or other “anti-American and racist theories.” Schools that do not abide by the restrictions could lose 5% of their state funding.

MICHIGAN–Nearly four in five Michiganders oppose politicians banning books in schools and believe it’s un-American to do so, according to a new Courier Newsroom/Data for Progress survey.

More than 78% of Michigan voters agree that “state lawmakers banning books at schools is a form of censorship and goes against American values of freedom of speech and expression,” according to the survey. Seventy-nine percent said they strongly or somewhat opposed lawmakers banning books in schools, while only 21% support such bans.

The results are in line with other polls highlighting the deep unpopularity of the Republican-led book ban movement.

Over the past 18 months, conservative activists, media, and politicians have stoked panic among some parents that public school children are being taught “Critical Race Theory” (CRT), an academic legal framework that studies the impact of systemic racism in the United States at the graduate school level.

CRT is not taught in K-12 schools, but that hasn’t stopped Republican leaders in state legislatures and school boards from rushing to ban books, censor how educators can teach about race and American history, and push curriculum transparency bills that critics believe are intended to instill fear in teachers.

In Michigan, Republican state lawmakers introduced bills last year to limit how Michigan educators talk about history and racism.

One bill, which passed out of the state House in November, would ban schools from teaching CRT, material from the New York Times’ 1619 Project on the origins of slavery, or other “anti-American and racist theories.” Schools that do not abide by the restrictions could lose 5% of their state funding.

Another bill, currently sitting in a state Senate committee, would effectively prohibit educators from discussing the ways in which a person’s gender or race, and the discrimination they suffer because of it, might make them see the world differently.

Both bills are opposed by the Michigan Civil Rights Commission, the State Board of Education, and the Michigan Education Association (MEA). Many parents and teachers also oppose the bills.

Trina Tocco, a mother and the director of Michigan Education Justice Coalition, believes the proposals represent an attempt to cover up the darker aspects of American history.

“I want my kids to learn as much as possible from as much history as possible so that they can learn and do better,” she recently told The ‘Gander. “I would prefer them to actually learn even the things that I don’t agree with. I want them to learn all of it, so that way they can be better people when they become adults.”

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, a Democrat, is likely to veto both bills should they pass the legislature, but teachers are worried about the bigger-picture impact of this crusade against the teaching of history and race.

“I think that this is actually just an attempt to whip up fervor and anger in the public. I think it’s a bogeyman and we’re so divided now along so many lines that it’s inevitably going to work, sadly,” said Zeinab Chami, an English teacher at Fordson High School in Dearborn.

More recently, Michigan House Republicans introduced a bill that would require public schools to make a list of all curriculum, classes, textbooks, literature, research projects, writing assignments and planned field trips easily accessible before the school year begins. Like the bill that aims to limit how teachers cover history and racism, school districts that fail to comply would lose 5% of their state funding.

Chami said this change would make it “almost impossible to be effective” in the classroom.

“I don’t teach curricula, I teach students, so I don’t have my curricula prepped a year ahead of time. I’m changing minute-by-minute,” she said. “Being a teacher requires [you] to be extremely nimble and responding to the students in front of you. Meaning today, my first hour looks very different from my fifth hour, even though they’re the same class.”

Greg Talberg, a social studies teacher at Howell High School, criticized the bill as a “solution in search of a problem.”

“They have spent the past year telling everyone to be afraid of CRT even though it wasn’t part of school curriculums to begin with,” he said. “Now that they have created a sufficient amount of unwarranted fear and skepticism, they follow up with unnecessary legislation that serves to further amplify fears, divide communities, and undermine the important work being done by students and educators.”

Sponsors of the bill argue it’s merely intended to help parents get access to information about their children’s education and prevent teachers from indoctrinating students on race and other issues with “radical” ideas, but parents like Tocco aren’t buying it.

She said that she gets weekly emails from her children’s teachers describing the topics and subjects they learned and believes most teachers do that, at least for younger students. “I’d love to know what it is that parents don’t feel like they’re getting from schools right now,” Tocco said.

Even if the bill fails, Tocco worries about what it represents.

“My kid came home the other day … truly interested in the story of Anne Frank,” Tocco said. “And it just dawned on me, I was like ‘My God, could it be that in a couple of years from now none of this is allowed in our school?’”

Survey Methodology: Data for Progress estimates opinion at the state level using a machine learning model trained on nationally representative survey responses linked to a commercial voter file. The model accounts for over 400 variables, including individual demographic characteristics, vote history, and primary participation as well as the political and demographic characteristics of the respondents’ census tract.

Politics

Whitmer expands clean water plan while enviros call for more clean energy investments

BY KYLE DAVIDSON, MICHIGAN ADVANCE MICHIGAN—As construction workers at the Delta Township Wastewater recovery facility continued efforts to expand...

Michigan Dems push for action on prescription drug board bills

BY KYLE DAVIDSON, MICHIGAN ADVANCE MICHIGAN—Four Democratic House members are renewing the call for action on prescription drug affordability,...

Local election workers fear threats to their safety as November nears. One group is trying to help.

TRAVERSE CITY—The group gathered inside the conference room, mostly women, fell silent as the audio recording began to play. The male voice, clearly...

Local News

These students are protecting the ‘coral reefs’ of Michigan—and you can too

Vernal pools are a critical part of Michigan’s natural ecosystem—but they’re not protected by state regulations. Here’s how Michiganders are...

The food at Comerica Park puts peanuts & Cracker Jacks to shame

Gone are the days when peanuts and Cracker Jacks were the most exciting food items at baseball games. Baseball stadiums around the country now boast...