Invasive sea lamprey populations are on the rise, posing a threat to the environment and economy—but scientists have a plan.

Need to Know

- Travel restrictions prevented regular predator control initiatives in the Great Lakes.

- Some fear that invasive sea lamprey could seize on the opportunity.

- Scientists are confident they’re more than prepared to prevent a crisis.

ANN ARBOR—A nightmarish invasive species that once sent tremors throughout the Great Lakes ecosystem is poised for a miniature comeback, scientists fear, after the COVID-19 pandemic indirectly disrupted control programs for sea lamprey.

But even as experts worry about the prolific parasites, nicknamed “vampire fish,” they believe they’re well-equipped with a “silver bullet” treatment to quickly contain any population jump and prevent them from wreaking long-term disruption on the ecosystem.

“We’re cautiously optimistic,” said Marc Gaden, legislative director for the Great Lakes Fishery Commission.

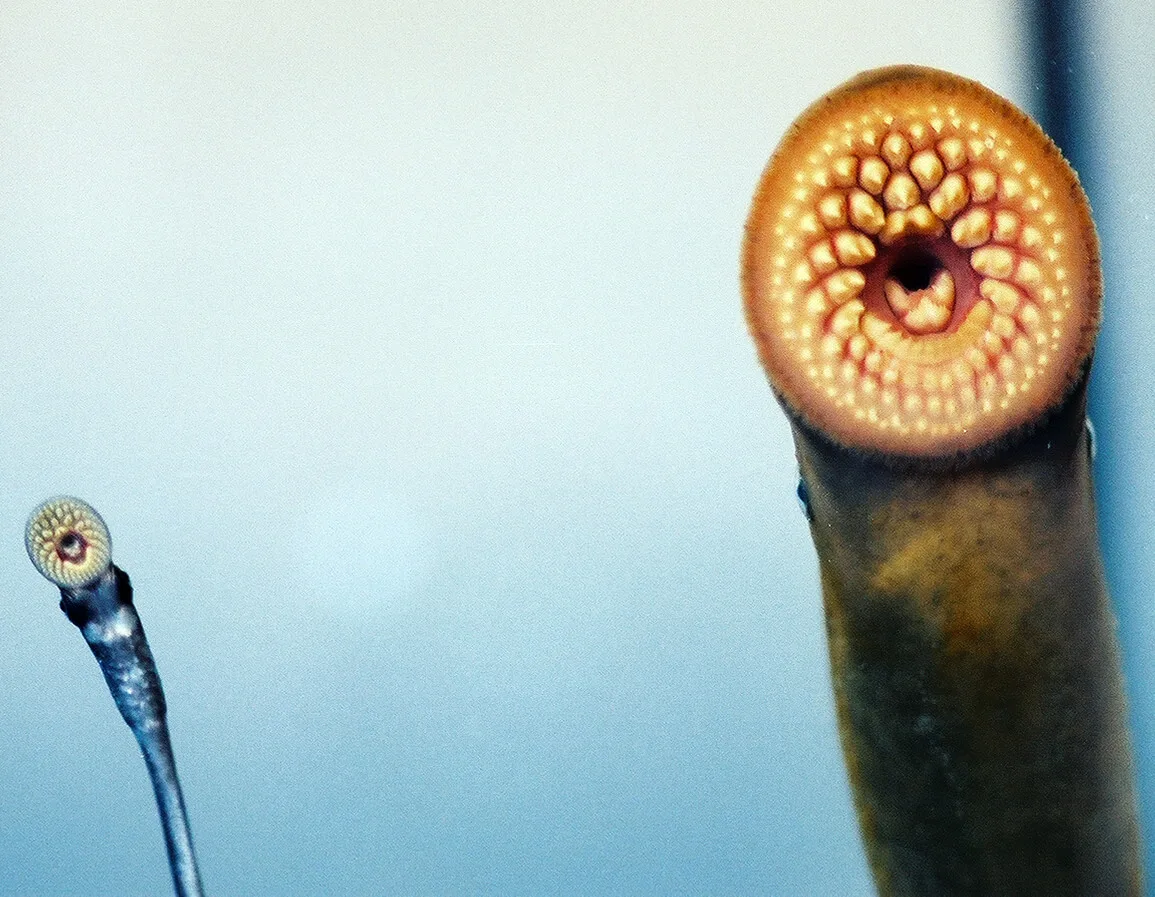

Sea lamprey are about as bone-chilling as screenplay ghouls; they’re vampiric by nature, parasitic top-down predators in the Great Lakes that suck the blood of fish. Their bodies resemble the slender frame of an eel or snake, and they attach themselves with piercing, spiraled teeth and hang on to their defenseless prey.

“They’re very destructive,” said Gaden. “They’ll latch onto the side of the fish. The mouth is a strong suction cup; it’s ringed with sharp teeth and anchored. And then there’s a file-like tongue that flicks out and it forces through the scales and the skin.”

But perhaps lampreys’ most horrifying quality isn’t their jagged teeth or suction-cup mouth, but how prolifically they reproduce. Female lamprey carry 100,000 eggs to deposit in nearby streams before they die, representing a particularly acute challenge for scientists who are desperate to keep their number under control.

During the pandemic, teams from the fishery commission couldn’t travel to areas where lamprey spawn; therefore, they were unable to distribute the chemical they use to control populations in streams filtering into the Great Lakes. The threat of rapid reproduction looms large over the freshwater ecosystem.

Lamprey once dominated the Great Lakes. As an invasive species without a predator above it on the local food chain, they devastated native species’ populations in the 20th century and ran local fishers out of business, taking five times the size of the commercial catch.

But after discovering a water treatment that would kill lamprey larvae but no other fish, the fishery commission cut their numbers to manageable levels. Heading into 2020, all of the Great Lakes were at or below their target for lamprey—thresholds established to create a balance to promote fishing and sustain a healthy ecosystem where native fish could once again thrive.

Although pandemic-related travel restrictions prevented teams of Canadian and US scientists from administering lampricide in lamprey-breeding grounds, those scientists are confident that they’ve got enough of a head start to keep numbers low. A temporary bounceback shouldn’t change the big picture, in which lamprey have been relegated to a secondary threat.

“We kept ’em down for 60, 70 years. That’s amazing,” Gaden said.

Horror on the Water

In the 20th century, horrified observers witnessed a slow-motion migration as these nightmare-fuel parasites snaked their way from the Atlantic Ocean through a network of canals over a period of years. At first, the sea lamprey were stumped by Niagara Falls, but with a canal built around the natural barrier, they sank their teeth on the Great Lakes, first reaching Lake Michigan in 1936 and in three years establishing a presence in Lake Superior.

In the 1940s and 1950s, sea lamprey wrecked the population of native fish—including whitefish, lake trout, and lake sturgeon, but also other local species—killing nearly 100 million pounds worth in total. Hundreds of thousands of sea lamprey thrived in the Great Lakes, where they had no predators but ample food. As lamprey use inland rocky or silty streams to deposit their eggs, the Great Lakes basin provided a perfect environment for them to multiply, better than even their original habitat.

The population spike spelled environmental catastrophe and economic disaster. Dead fish washed ashore constantly, with circular puncture wounds, the scene of where lamprey had drained their blood and left them to die. The parasites leeched catch from fishermen, who themselves noticed a slump in their haul, and governments had to find ways to be more intentional about protecting native species.

Just years before the lamprey invasion, commercial fishing was one of Michigan’s preeminent industries. Tens of thousands of people made their livelihoods off commercial fishing and harvested the maximum amount of fish they could—but the state noticed a marked drop in fish populations from years of overfishing. The invasion of lamprey, alongside other species, exacerbated the issue, and governments reeled in the number of licenses and sizes of allowable harvests, driving down the number of people in the business.

In 1954, as circumstances worsened, the US and Canadian governments launched a sea lamprey control initiative, under the guidance of the Great Lakes Fishery Commission.

After 10,000 trials of different chemicals and pesticides, the commission found its secret weapon—a lampricide that targeted the invaders but didn’t harm other fish. Lamprey numbers fell rapidly, and the commission has been applying that same treatment, known as TFM, since.

To date, the treatment has done wonders in rehabilitating populations of native species and reducing lamprey populations by 90 to 95%. The number of fish lost to lamprey, which at its peak exceeded the number of fish allowed to be caught, has dramatically shrunk, also by 90%.

“We joke, if they looked like puppies or bunnies, it might be a little more difficult to get the social approval to remove them,” Gaden said. “But they speak for themselves.”

Even today, the commercial fishing industry is a shadow of what it once was, with only 50 or so licensed commercial operations in Michigan. But in its place, at least somewhat, the recreational fishing industry has filled an economic and cultural void, generating some $2.3 billion in impact for the state. The Great Lakes fishery is still worth more than $7 billion and powers more than 75,000 jobs.

Still, some fish populations, like lake sturgeon, are on the mend after decades of irreparable damage from overfishing, lamprey, and other invasive species. A study in 2004, even after the lamprey problem shrank, found that 22% of lake sturgeon were found with lamprey wounds in the St. Marys River. As the population recovers, anglers are allowed to catch only one lake sturgeon a year and must do so in certain areas.

The Predators Strike Back

In 2020, when travel restrictions walled off US and Canadian colleagues from each other, work stagnated. Unable to handle bigger rivers with small, disjointed teams, the Great Lakes Fishery Commission carried out only about 30% of the scheduled number of treatments that year, as the pandemic began right before they planned to go out on the water.

Those untreated areas could give rise to new generations of lamprey that wreak havoc in the Great Lakes and then head back to streams to spawn.

In 2021, the team was able to better coordinate and plan its treatments, but still missed out on a quarter of what its usual goal would be because of travel barriers.

“This is a boots on the ground program and boats in the water,” Gaden said.

The pandemic isn’t the only time that treatments have had to be delayed, as weather events and external circumstances have gotten in the way before. But the level of disruption from COVID-19 posed a special challenge, and people will soon see what the fallout is from the case.

With breeding cycles of every few years, the next generation of lamprey might come in large numbers to the Great Lakes soon.

Not Perfect but on Track

Now in 2022, the commission is back on track, set to administer 100% of treatments and make up for lost time. They’ll be back on the water soon.

“We’re not scratching our heads wondering how to deal with it,” Gaden said.

There’s good news and bad news, Gaden said.

The bad news is obvious: Lamprey populations might swell, as the larvae that hatched in untreated streams forge ahead to bigger waters.

But the good news is that the problem at hand isn’t anything like the horror days of when lamprey ruled the Great Lakes. Numbers are well below goals established by state and local governments, and Gaden expects it to remain that way, even if lampreys have a good year.

A. Miehls, GLFC

For the decade up until COVID-19, the commission had received additional funding from Congress for lamprey control initiatives. Now, lamprey numbers are under control, and native fish should be able to survive a pandemic-related blip.

“We were as well-positioned as we could have been for this unanticipated, unpredictable disruption,” Gaden said.

At this point, there’s no hope of wiping out lamprey invaders totally, Gaden said. Once they’re here, they’re nearly impossible to get rid of.

It’s the law of diminishing returns and a simple cost-benefit. Getting those first 10,000 lamprey is a lot easier than getting those last 10,000, who might spawn in smaller streams or whose young find a way to escape the lethal lampricide. Instead of exhausting resources, the commission has found it more effective to rehabilitate native fish populations that were hampered by lamprey invasion and reinvest in the environment.

All of this has taught—or more accurately, reinforced—a lesson for preserving and protecting an ecosystem. Simply, it’s easier to prevent a species from getting in than control it once it’s there. It’s also cheaper and more effective.

In other words, bringing resources to bear against invasive species now could save the lives of native species and the jobs of local people in the long run. As policy-makers and officials form their Great Lakes strategies around invasive species, like the pressing threat of Asian Carp, they should keep the lesson of the lamprey in mind, Gaden said.

“Let’s keep the carp out,” Gaden said.

Politics

It’s official: Your boss has to give you time off to recover from childbirth or get an abortion

Originally published by The 19th In what could be a groundbreaking shift in American workplaces, most employees across the country will now have...

Michigan Dems win special elections to regain full control of state government

LANSING—Democrats won back a majority in the Michigan House and restored their party's full control of state government Tuesday thanks to victories...

Trump says he’s pro-worker. His record says otherwise.

During his time on the campaign trail, Donald Trump has sought to refashion his record and image as being a pro-worker candidate—one that wants to...

Local News

That one time in Michigan: When we became the Wolverine State

How did Michigan become tied to an animal that's practically nonexistent there? Among the many nicknames that the state of Michigan has, arguably...

Readers’ Choice: Top 5 Bowling Spots in Michigan

From retro lanes — including one of the oldest running bowling alleys in the country — to modern entertainment centers, there's something for...