Ruins of an abandoned stone building in a mining complex in the Keweenaw National Historic Park in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan (Shutterstock)

These are seven ghost towns you won’t believe were once booming.

MICHIGAN—Central Mine’s popularity was on the rise.

One of many mines that opened in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula in the mid-to-late 19th century, it was easily one of the area’s fastest-growing copper mines. The first 40 feet of the mine turned up over 40 tons of copper, and it was the only mine in the region to turn a profit during its first year.

The success led to swarms of people joining the mining industry. A community formed around the mine, and soon enough Central Mine, as it was called, boasted a population of more than 1,300. It had a church, a school, a post office, and one of the top telephone services in the area.

But then everything changed. As quickly as the mining industry took off, it quickly became obsolete. By 1905, the mining town was home to fewer than 100 people. It had met the same fate many Michigan mining towns met in the early 1900s, turning from a once booming community to a ghost town.

Michigan, believe it or not, is home to dozens of these ghost towns, communities that once were lively but quickly were erased from the map. But perhaps no part of the state is home to more of these abandoned communities than the Keweenaw Peninsula, home to the state’s mining boom as well as its turn away from the now mostly defunct industry.

Below are some of that region’s most popular ghost towns. Some are completely abandoned, while others remain the homes to a handful of summer cottages.

Baltic

If you ever find yourself driving north on M-26, heading to one of the popular breweries scattered across Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula, know that you can hop off the beaten track a short distance to find one of Michigan’s many forgotten communities: Baltic.

Baltic is about 6 miles southwest of Houghton and was once the home of the Baltic Mining Company. Exploration work for the underground copper mine began in 1882, leading to the discovery of ore.

While the mine switched hands a few times, as far as ownership was concerned, it served its purpose for some time before ceasing operations in 1931. Its deepest shaft traveled more than 3,800 feet into the earth, and the mine as a whole produced nearly 300 million pounds of copper during its 34-year history.

Bete Grise

Bete Grise is another once important mining village that remains as a reminder of a once crucial part of Michigan’s economy. It can be found east of US-41, at the end of an 8-mile stretch of winding road along the Lake Superior coastline.

Bete Grise, French for “Grey Beast,” is just that in Michigan’s later months. The harbor it sits near is often a safe haven for Great Lakes boats in October and November, when the weather takes a turn for the worst. The old town is also home to the Mendota Light Station, from which people can see beautiful Michigan scenery and beaches.

As of 1940, only about 10 people lived in the town. Its buildings were left behind, but many still stand as they did then. While it serves as a sort of destination for some people traveling up north, much has been done to keep the place as it once was. A housing development slated for the area’s beaches was shut down in the early 2000s.

Central Mine

The community built around Central Mine, which was once one of Michigan’s fastest-growing copper mines, remains a popular part of Michigan history, thanks in part to the Keweenaw County Historic Society Museum Complex. The mining town, once home to more than 1,300 people, is still home to a few vacation cottages, but for the most part is your standard Michigan ghost town.

The area, which can be found just north of US-41, about 4 miles north of Phoenix, was settled in 1854. In 1887, it reached its peak population size, with more than 1,300 people living in the community. But by 1905, that number had dropped to fewer than 100.

Today, the area is open to tourists. Many buildings that were once homes to miners and their families have been restored, and there are also a memorial garden and other buildings open to tourists.

Craig

On the shore of Keweenaw Bay, at the mouth of the Portage River, the community of Craig was founded around 1893. Built on the Soo Line Railroad, 13 miles southeast of Houghton, the community quickly grew. Within four years of being established, the town was receiving mail every other week—a feat for young communities in the Upper Peninsula.

Ten years after its inception, Craig had grown to 200 residents. Mail was now arriving every day, and the community even had its own general store. But in a little over 10 more years, that all changed. The post office closed, and the community became another of Michigan’s ghost towns.

Delaware

If you take US-41 north—about 10 miles north of Central Mine—and look to the right, you might find yourself staring at the remains of a once booming mine town. You just might not realize it.

Delaware is another lost mining town. What remains? Old houses, buildings, and a few other remnants of what once was. The community was previously home to about 1,100 people and had its own court system, having grown since its development in 1846. But by 1893, only 25 people still called the place home.

Freda

Freda was a late bloomer, forming in the Keweenaw Peninsula in 1910. It grew to a population of 500 people and eventually had a church, a doctor, and a hotel. The Catholic Church made its way to the northern Michigan community in 1917, the same time the community got its own movie theater.

Over time, as the mining industry took a hit, so did Freda. The community, which also served as a popular resort town for some time, eventually was severed from most of civilization. In 1971, the once popular Copper Range Railroad rails into town were removed. The town mill, similarly, was closed up, and Freda became another Michigan ghost town.

Mandan

Mandan can be found less than a handful of miles north of Delaware, the old trail that leads to the abandoned town marked by a sign on US-41.

But the town, which once had its own school, doctor, and more than 300 residents, offers much less these days. The community was founded in the mid-1800s near two mines, but as time went on, the town saw a quick drop in its population. In 1909, the mines were abandoned and, in 1915, about 25 people lived in the community.

Politics

SEIU workers ahead of NFL Draft: We are ‘the backbone of Detroit’

BY KEN COLEMAN, MICHIGAN ADVANCE MICHIGAN—A day ahead of the National Football League annual draft being held in Detroit, Service Employees...

Investigator says Trump, allies were uncharged co-conspirators in plot to overturn Michigan election

DETROIT—A state investigator testified Wednesday that he considers former President Donald Trump and his White House chief of staff to be uncharged...

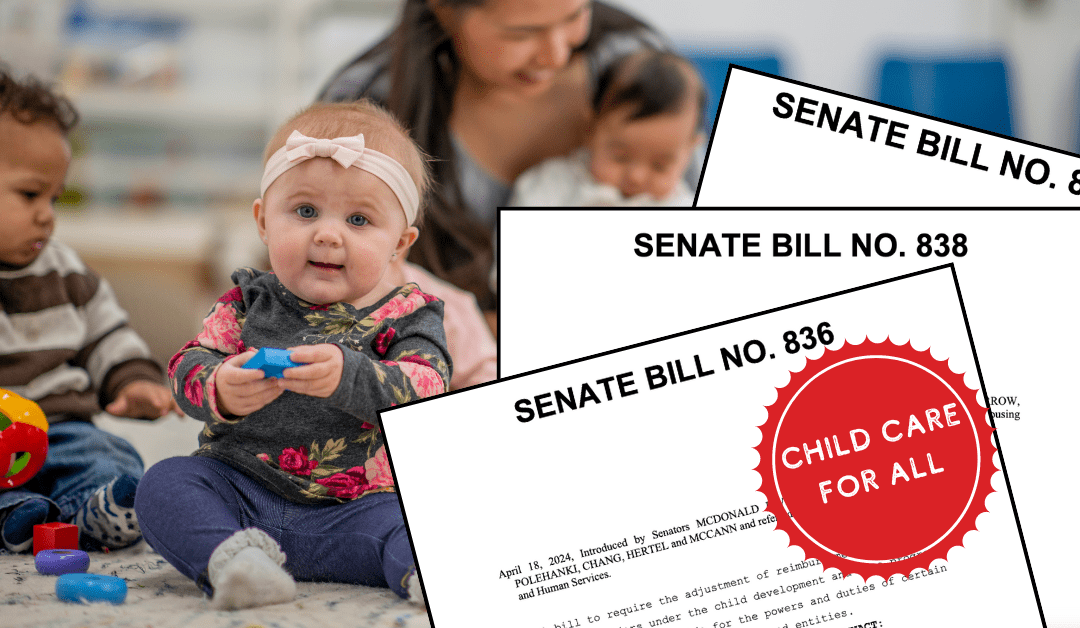

Michigan Dems introduce ‘Child Care for All’ legislation to lower costs for families

Lawmakers say Michigan is facing a ‘child care crisis.’ But a series of bills introduced this month would help to make child care (much) more...

Local News

The 10 best burger joints in and around Lansing

Warning: Do not read this list if you missed lunch or you will find yourself hopping in the car to drive to these best burger joints in Lansing. ...

10 unique wedding venues in Michigan to suit every kind of couple

From a distillery in Detroit to a summer camp, we’ve rounded up some of Michigan’s most unique wedding venues. Of all the elements you need to...