As Angelina sweeps her walking stick across the forest floor, combing back the untamed foliage, I scan the area. I’ve been told to look for little brown caps rising from the undergrowth. I excitedly point one out, but it’s just a dead leaf. Angelina tells me that’s normal.

I spend a lot of time in the woods, usually for wildlife photography. I think I have a pretty good eye for what’s happening underfoot, but five minutes into our hunt I realize that if I’ve ever seen a morel mushroom, I most certainly walked by without a second thought. Today, I’m determined to find at least one.

We’re in the woods of Southwest Michigan, following a little deer path through the foliage, ducking under branches and climbing over logs. Where, exactly? Angelina won’t say on the record. Many mushroom hunters keep their spots a secret. What I can tell you is that out where we are, our only competition is the local deer. Sure, you can find mushrooms in public parks, but so can everyone else, and with the hobby increasing in popularity—especially with young adults—I get why Angelina wants to keep her spot to herself.

Angelina Bertoni, 30, is a West Michigan Realtor, photographer, and fire thrower. As we walk, I pester her with questions about all of these things. She answers with fascinating stories, but the deeper we get into the woods the more I realize that her love of nature perhaps outshines all.

Along for the ride is Rowan, Angelina’s one-year-old poodle. He’s in training to sniff out morels, and found three last weekend. But today, he’s more interested in finding the perfect stick. He’s got a lot to choose from.

Angelina’s quick to point out various plants and fungi, both edible and not. I stoop down to smell wild chives. I sample a honeysuckle bud, a wild black raspberry leaf, and a purple lilac flower. All common Michigan plants, each with its own season, taste, and uses. As delightful as these are, they’re not what we’re after. We press on into the woods, until a certain gleam hits Angelina’s eye. This is the spot. Our search for morel mushrooms begins.

WHAT IS A MOREL? Angelina tells me it’s one of many edible mushrooms here in Michigan. Their light to dark brown caps are porous, with irregular holes. Think of a bee’s honeycomb if the bee had been drunk. Sitting atop lighter-colored stems, they poke out inconspicuously from the forest floor. Often hidden by the undergrowth, it’s easy to walk past one without even realizing. Really, really easy.

Morels are far from the only edible mushroom in Michigan. There may be as many as 100 edible mushrooms in the state, in addition to lots of inedible and toxic ones. Growing from the side of a log, Angelina points out a mushroom called “pheasant’s back.” It’s a light-colored, flat, disk-shaped mushroom. Angelina says that after scraping off its tough outer pores with a knife, it’s delicious sautéed.

Later in the summer, a mushroom nicknamed “Chicken of the Woods” (for its similar taste to chicken) will also be available for foraging. But lest I start to think that every mushroom is a meal, my guide tells me that many are downright dangerous. At least 50 of the larger species in Michigan are poisonous, and their effects range from mild discomfort to death.

WHAT ISN’T A MOREL?

Angelina’s number one rule: Never harvest a mushroom you can’t 100% identify. This is especially important when hunting for morels. “Imitation morels” resemble the ‘shroom we’re here to find, but are toxic to humans. As Angelina harvests the first morel of the day, she explains that a good way to tell if a mushroom is a true morel is by its hollow stem. (Imitation morel stems are solid.) She hands it to me and I look into the mushroom’s hollow stem; there’s a pill bug there to greet me. After gently evicting the pill bug, I notice how spongy and alien the morel feels in my hands. Angelina says it’s a big one; probably four or five days old and toward the end of its lifespan.

WHERE AND WHEN TO HARVEST?

We’re in a shady gulch, under a few large oak trees. There’s a lot of undergrowth. Dark. Damp. This is a prime morel spot.

Angelina explains that morel mushrooms grow in specific conditions: Moist, but not too wet. Warm, but not too hot. They often grow near water, but not if it’s muddy. To demonstrate this further, she has me feel the soil in this shady area, and then in a sunny clearing just a few feet away. By grinding my boot into the dirt, I feel the difference. Where the shaded area is moist, the sun sucks all the moisture from the clearing. The surrounding large oaks and frequent hills also help, as both hold in mushroom-friendly moisture.

Time of year matters, too. From the end of March to the beginning of May, morels start popping. One early week of hot weather, though, can kill off a lot of morels. A long winter can push back their start. And morel season in the southern Lower Peninsula can be over and done before the things really get growing in the U.P.

Wherever you are in Michigan, a good time to start looking is after the first few consecutive days of warm (not hot) temperatures, especially after rain. Think high 50s to low 70s. On the mid-May day of my hunt with Angelina, she says it might be the last week of the year for our location. Challenge accepted, Angelina.

HOW DO YOU HARVEST?

She finds another morel, and as soon as she points it out I wonder how I missed it. Using a purple pocket knife, she cuts it close to the base of the stalk. She’s careful to leave a little behind—the stalk will release spores, which means more mushrooms will grow in the area. A morel can grow more of itself twice a season, so it’s worth checking the same spot twice. That also means that if you find one morel, there’s a good chance there’s more nearby.

As she puts the mushroom in her basket, Angelina points out holes in the basket’s weaving. The morels we’re carrying release spores through the holes as we walk, she says. Local deer do this too—they eat the mushrooms and release spores along their paths. By following their example, we’re not just taking from the woods. We’re a part of it.

Angelina stresses how important this is. “If everyone goes out and starts taking them, we’re not going to have any.”

“THE HUNTER-GATHERER MENTALITY”

That’s how Angelina describes what we’re doing, and out here, with no modern society in sight, it’s easy to feel why. “This is the way people used to eat,” she says.

Along with mushrooms, we pick up any litter we find. “The more trash you pick up, the more mushrooms you’ll find.” It sounds silly at first, but bending down to pick up a piece of litter gets you eye-level with the mushrooms.

It’s a saying Angelina learned from her mother, who taught her mushroom hunting when she was three years old. Angelina says she appreciated these outings more as she grew older, and attributes much of her skill to her mother. “She helped make me the woman I am because she took me into the woods.” To Angelina, it’s not just about finding mushrooms, it’s about being connected with nature and the world around her. Following in her mother’s footsteps, she frequently teaches her friends to forage. She still forages with her mom, too.

It’s impossible not to feel a kind of profundity settle around us, as Angelina walks the narrow deer path and talks about nature. “There are more treasures than just mushrooms,” she explains. Animal tracks and bones, interesting insects, and the general awe of nature can be prize enough. A well-timed owl hoots overhead, and I get chills.

That’s when it happens. Very casually growing just off the trail, a morel reaches out to me. I’m surprised Angelina didn’t see it first (maybe she did) but I’m overjoyed to take the win. I hold my face to the dirt and smile as Angelina takes my picture, and then I cut the mushroom from the ground. It even has a hollow stem—a true morel; a tiny jackpot from nature.

And with a gambler’s itch, I can’t wait to find another. Angelina says that feeling never goes away. Before I know it, I’m obsessively searching the surrounding hillside. The rest of my day is spent pacing and squatting on the forest floor, trying to spot that fungal diamond in the rough.

EATING MORELS

A quick web search brings up a lot of morel recipes, but Angelina gives me a simple one: Sauté with butter or olive oil, and onion if you want. She says morels are nicknamed “dryland fish” for their delicate, fishy taste. Before you can cook them, they must be cleaned.

Back in the city, I do just that. Using a simple homemade cleaner (boil salt water, then let it cool), I gently wash the dirt from the morels in my sink. I cut them up, and cook them with butter and onion. As I hold one to my mouth, I have a moment of skepticism. Am I really about to eat something I just got off the ground? My first bite ends all doubts. It’s rich, yet delicate. Primal, yet wholesome. Is it profound? I don’t know. But there’s a story in this mushroom.

Politics

Michigan lawmakers look to break (another) state funding record for public schools

Democratic lawmakers are hashing out plans to bring state funding for Michigan’s public schools to another new, all-time high—and ensure teachers...

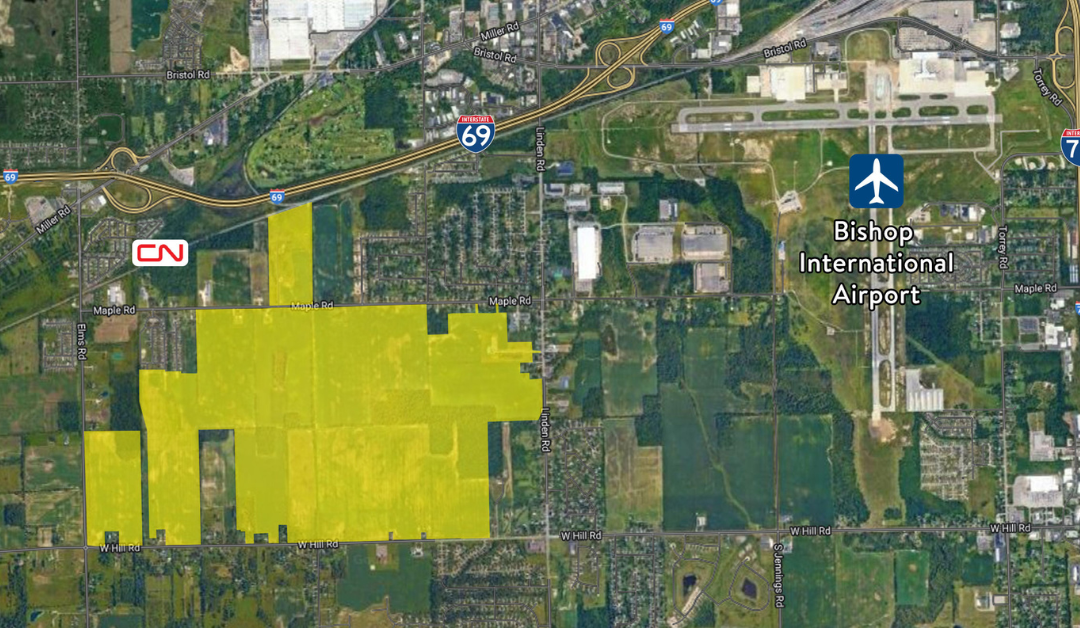

Mundy Twp. project gets state funding in effort to boost local manufacturing

More than $9 million awarded to a planned development project in Genesee County could provide a big boost to the local economy and help create...

It’s official: Your boss has to give you time off to recover from childbirth or get an abortion

Originally published by The 19th In what could be a groundbreaking shift in American workplaces, most employees across the country will now have...

Local News

More Michigan teens could soon take driver’s ed in their own schools

Privatization of driver’s education means that only 38 Michigan high schools offer affordable in-school driving classes for students. New grants...

That one time in Michigan: When we became the Wolverine State

How did Michigan become tied to an animal that's practically nonexistent there? Among the many nicknames that the state of Michigan has, arguably...