Kristen Eichamer, right, talks to fairgoers in the Project 2025 tent at the Iowa State Fair, Aug. 14, 2023, in Des Moines, Iowa. With more than a year to go before the 2024 election, a constellation of conservative organizations is preparing for a possible second White House term for Donald Trump. The Project 2025 effort is being led by the Heritage Foundation think tank. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall)

With the 2024 presidential election less than a year away, conservative activists have crafted an expansive blueprint that lays out in detail how they intend to leverage virtually every arm, tool, and agency of the federal government to attack abortion access—including by banning and criminalizing access to abortion medication.

That plan—which is more than 900 pages long—was put together by allies of former President Donald Trump and includes ways to make abortion inaccessible without actually passing any new laws at all.

The theory: Trump could replace nonpolitical staff in government agencies with right-wing loyalists who exploit the power of these agencies to erode abortion rights. He could, for example, hire staff at the US Food and Drug Administration who reject medical science and reverse the agency’s approval of all abortion medication.

Project 2025, as the plan has been called, also calls for allowing emergency rooms to refuse to perform life-saving abortions, reversing HIPAA privacy protections for patients getting abortions, and directing the US Department of Justice to start enforcing the Comstock Act of 1873. The old law bans the mailing of “anything designed, adapted, or intended for producing abortion,” which would include not only abortion pills, but potentially medical instruments.

Under such an interpretation of the Comstock Act, any clinic that gets supplies shipped across state lines could be found in violation of the law, even those in states that have protections for abortion in the state constitution.

In other words: Republicans could use Comstock to target abortion providers in all 50 states—effectively wielding the law to implement a national abortion ban of sorts. They could even use the law to prosecute women who possess abortion pills.

So, what exactly is the Comstock Act, why does it matter, and who came up with it?

Anthony Comstock and the Comstock Act

The Comstock laws are a set of regulations that criminalized “obscene” materials over 150 years ago.

Anthony Comstock was an “anti-vice” activist who believed that the mere existence of birth control, abortion, pornography, sex, and even nudity in art corrupted society.

In the late 1860s, he started supplying police with information for raids and on sex trade merchants. It was around this time he identified the contraceptive industry as another one of his targets, the first step in his becoming of a driving force behind the original federal anti-birth control statutes.

In 1872, he traveled to Washington with an anti-obscenity bill he drafted himself. The bill included a ban on contraceptives. By March 2, 1873, Congress passed the law, which came to be known as the Comstock Act. Because Comstock was appointed as a Special Agent of the US Post Office that year, he had the authority to enforce his laws.

The Comstock Act defined contraceptives as “obscene” “lascivious” and “illicit,” among other adjectives. The law made it a federal offense to disseminate birth control across state lines or through the mail, and gave the post office authorization to search for pornography, and “information or items related to sexual health, sexuality, abortion, and birth control.”

Because the law’s definition of what was “obscene” was so broad, the post office had the authority to seize novels, plays, art, medical textbooks, and even personal letters.

State Laws, Margaret Sanger, and United States v. One Package

Soon after the law was passed, 24 states enacted their own versions of Comstock laws. The harshest legislation existed in New England, where those found guilty of violating these laws faced large fines and imprisonment. In Connecticut, the simple act of using birth control was prohibited by law, and married couples could even be arrested and face one year of imprisonment for using contraception.

The laws remained on the books and unchallenged until Margaret Sanger, an activist, sex educator, and nurse, made it her mission to challenge the federal Comstock Act. Sanger was arrested in 1916 for opening the first birth control clinic in America; her arrest led to the 1918 Crane decision, a New York state court case which allowed the use of birth control for therapeutic purposes and for the prevention of disease.

In 1936, the US Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that doctors could distribute contraceptives across state lines in United States v. One Package. Although the decision did not eliminate “chastity laws” on the state level, physicians could now legally mail birth control devices and information throughout the country.

This decision ultimately led to the enforcement of the Comstock Act being dropped. It’s also widely believed that this court decision paved the way for contraceptive legitimization within the medical industry and acceptance within the general public.

Do Comstock Laws Still Exist?

Kind of, but they don’t legally impact abortion care.

While the laws were in place, they started to be enforced less, similar to The Volstead Act, which prohibited the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages. Over time, the demand for alcohol began to outweigh the demand for sobriety. Like alcohol, you can’t keep humans away from sex.

In 2022, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, which guaranteed the constitutional right to an abortion. This allowed states to once again make their own laws regarding the procedure.

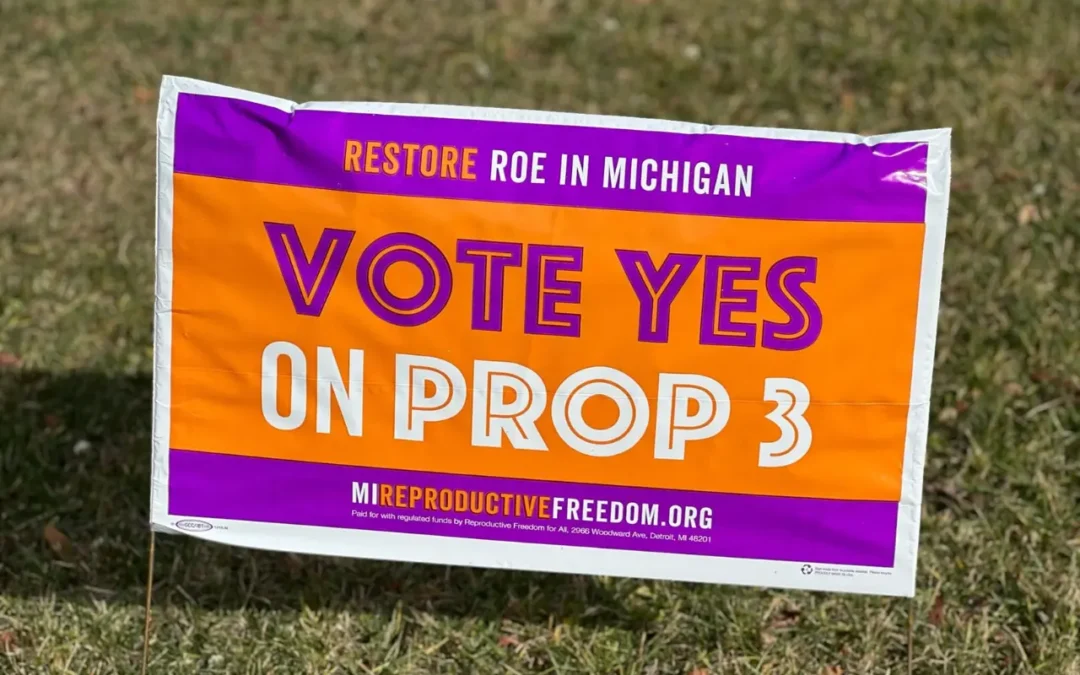

In Michigan, voters enshrined abortion protections into the state constitution last year, and thus, abortion is legal until fetal viability, which is usually around 23-24 weeks.

The Supreme Court decision also emboldened anti-abortion activists to claim that the Comstock Act could once again be used to criminalize the mailing of mifepristone.

The Comstock Act in 2024

Although the laws haven’t been enforced in over a century, they’ve been brought back into the spotlight due to US District Judge and Trump appointee Matthew Kacsmaryk’s name-checking of the Comstock Act in a April 2023 court decision.

Last year, Kacsmaryk sided with Christian conservatives who filed a lawsuit seeking to reverse the FDA’s 2000 approval of mifepristone, one of two pills used in medication abortions. The anti-abortion groups behind the lawsuit claimed as part of their case that the Comstock Act prohibited the mailing of mifepristone.

Kacsmaryk—a far-right judge with a history of anti-abortion views—ordered a complete hold of the federal approval of the drug, overruling decades of scientific approval precedents and hundreds of studies documenting the drug’s safety in abortion care.

A federal appeals court partially blocked Kacsmaryk’s decision, maintaining mifepristone’s availability, but limited access in ways that could harm patients seeking abortion care.

The Supreme Court then stepped in, ruling that the availability of mifepristone would not change as an appeal moves forward. The Supreme Court also agreed in December to hear the case, with oral arguments in Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine v. US Food and Drug Administration set to take place on March 26.

More than 600 state-level Democratic lawmakers from 49 states have signed an amicus brief to the Court urging the justices to maintain access to mifepristone and completely overturn Kacsmaryk’s decision.

In Michigan, over a dozen lawmakers signed the brief, including Rep. Laurie Pohutsky, Sen. Rosemary Bayer, and Sen. Erika Geiss.

Regardless of what the Supreme Court decides, health care access in the US will be altered.

If mifepristone is pulled from the market, doctors will be forced to prescribe just misoprostol, the second drug in the two-drug regimen that is prescribed to end a pregnancy, which has a lower rate of effectiveness when prescribed alone.

Legal experts have also warned that this case could “upend decades of precedent” and could “set the stage for political groups to overturn other FDA approvals of controversial drugs and vaccines.”

The Biden administration has said that it stands by the FDA’s nearly two-decade old approval of mifepristone, and that it’s “focused on ensuring access.”

Wakefield doula helping local moms as federal funding cuts impact the Upper Peninsula

As federal funding cuts cause more rural hospitals in the Upper Peninsula to close their doors, doulas like Lynnea Laessig of Wakefield are stepping...

Right to Life of Michigan files court appeal to challenge Proposal 3 claiming ‘dangerous overreach’

BY KATHERINE DAILEY, MICHIGAN ADVANCE MICHIGAN—Right to Life of Michigan, alongside several parents, have filed an appeal in the US Court of Appeals...

These two southeast Michigan moms want to fight for their communities—so they’re running for office

As Republican lawmakers try to cut maternal health care resources in Michigan and beyond, these ‘Ganders are pushing back—by trying to replace...

This Detroit community is helping its neighbors recover with abortion after care event

“At the end of the day, it’s going to be a community that pours into one another, especially when things get hard.” As attacks on abortion and...

Planned Parenthood extends telehealth to 7 days a week in Michigan due to growing demand

“For many of our patients, telehealth is literally lifesaving.” In response to the escalating attacks on sexual and reproductive health care...