It was an unspoken rule that you couldn’t take time off unless you needed to and had coverage. But that’s what was needed to reopen Michigan schools.

Need to Know

- Michigan janitors and custodians have skipped vacations to help reopen schools.

- From staggering classes to inventing new cleaning procedures, schools have adapted to contain COVID-19.

- Gov. Whitmer has proposed “hero pay” to reward essential frontline workers with between $1,500 and $2,000.

BERKLEY, Mich.—Vocabulary day has taken a spirited hold of Rogers Elementary School. March is National Reading Month, so kids bound through the halls with name tags pinned to their shirts, as they dress as whatever their word is.

One child, decked out in a green jersey and pants, is “emerald.” Another, with brown marker-colored paper taped to his upper lip, is “mustache.” The principal, Beth Meacham, sports a shirt with the bolded word “retired.”

To date on this Wednesday morning, exactly two years have passed since Gov. Gretchen Whitmer ordered schools to temporarily go online in order to prevent further spread of COVID-19. Last February, Rogers Elementary resumed class in person, but with half days and “cohorting.”

Keeping school safe and uninterrupted by virtual stints has been an all-hands-on-deck effort. But then again, it usually is at elementary schools, head custodian Lou Brunskill said.

“They wanted to be back,” Brunskill said. “They’re glad to be back.”

In the Berkley school district, masks are now optional. COVID-19 positivity rates have fallen to the point that the school board, in consultation with health professionals, deemed it safe—per regular community positivity rates posted to school dashboards.

Now that’s not to suggest that there are no other precautions at play.

The school still takes down data for contact tracing, though doing so is no longer required by the state.

Colorful polka dots, six feet apart, line the hallway carpets, demarking where students should stand as they come in on a rainy day.

Lunch breaks are taken in classrooms, not the cafeteria—all part of contact tracing, so that in the case of a positive, fewer students need to be sent home.

“It’s harder on the building, but it’s the right thing to do,” Brunskill said

And it’s working. Rogers Elementary hasn’t had a “major” outbreak yet, according to officials.

The kids almost feel like life is back to normal—if anything, they’re just happy to be back in person, done with virtual school and half-days.

“I think kids are probably the most resilient,” Jessica Stilger, the district’s communication director, said.

“Bingo,” Brunskill responds. “They wanted to be back.”

What the kids don’t realize that the three school custodians sacrificed vacation days to make sure class could resume in person, working exponentially as hard to regain a level of normalcy.

“We did what we had to,” Brunskill said.

Behind the Scenes

Working with children from kindergarten to fifth grade can be draining work, but the endlessly gregarious Brunskill seems unfazed by shrieks and sprinting as lunch begins.

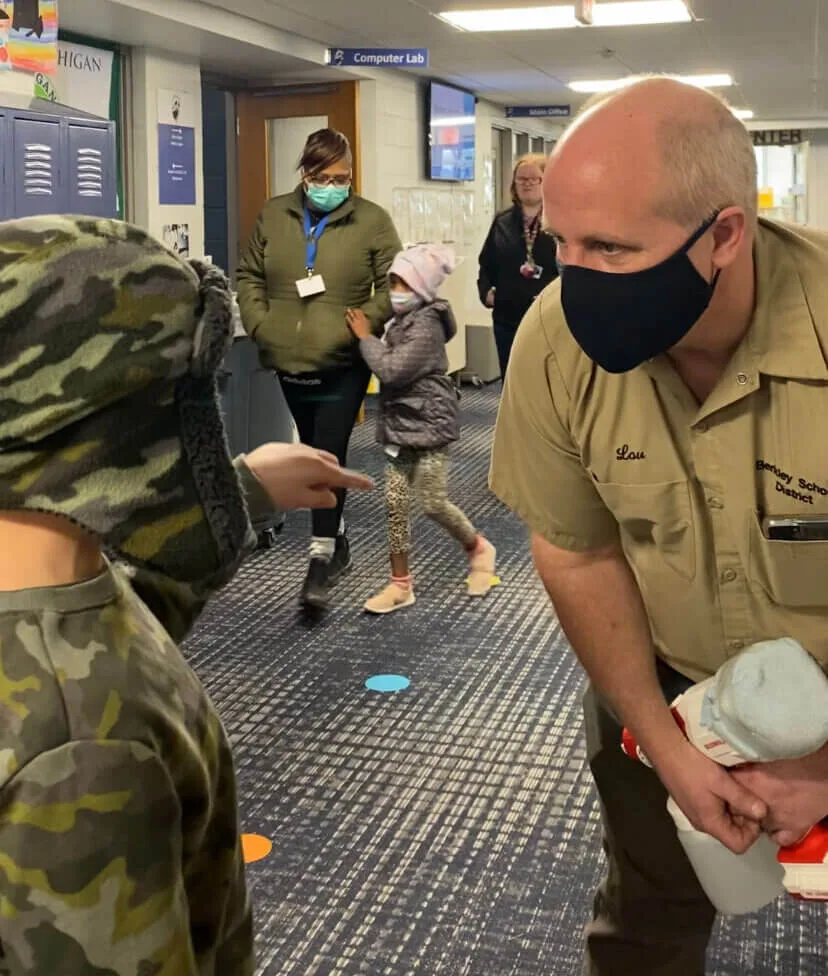

As he walks out of cleaning the boys’ bathroom, a little boy—dressed in camouflage pajamas, likely making him “soldier,” “camouflage,” or something of that genus for vocabulary day—pokes him on the shoulder.

Someone has drawn on a board with a sharpie.

“He drew on the very beginning of the board,” Camouflage says.

Brunskill bends down to answer and tells the boy he’ll get to it shortly. The request doesn’t seem to bother him.

Berkley school district has been Brunskill’s workplace for more than two decades. He’s been at Rogers Elementary for the past 11 years.

It’s a place that he’s seen and helped grow over decades. As he tours through the building, built in 1952, boasting about a new wing and glass-encased media center, Brunskill is like a proud father showing off his child’s artwork.

But it’s not just pride. It’s “ownership”—the slogan for the custodian team in the district.

That’s something that they preach in monthly meetings, according to Chris Smallwood, operations facilitator for the Berkley School District, much like a coach instilling an ethos into his team.

“They were all here in the buildings making sure they were taken care of,” Smallwood said. “That’s one of the things we talk about in our district is ownership.”

This isn’t a small school district—it’s actually ranked 19th in the state by education ranking site Niche—but it’s a tight-knit one, where feedback is a constant loop from the administration to staff. Being a custodian here doesn’t just mean disposing of trash.

In the winter, Brunskill plows, salts, and shovels.

On other days, he’s manning roof repair or trying his hand at plumbing.

Every day is something different. That’s just how he likes it.

WOMEN’S HISTORY MONTH: You Probably Don’t Know These 7 Female Historical Figures from Michigan

The Outbreak

When school first shut down, everyone went into scramble mode. Everyone effectively joined the IT department, shifting their focus to giving kids laptops and setting them up to attend school from home.

The next few months were chaotic as well. People still reported to the building, checking into the office, but the halls were quiet—everyone was home.

Then, for a few months, staff began to find their groove. For Brunskill, the absence of kids let him shift his focus from upkeep to upgrades—performing long-term improvements that he’d been meaning to get to but had previously never had the time.

During that time, the custodian staff also was working out how to sanitize and clean a school to protect against a pandemic that scientists were still coming to grips with.

They did the best they could to clean it day to day. But it was one thing to clean the school when faculty, families, and students were rarely ever there—it’s a whole different battle trying to clean the classrooms every day, with young kids shuffling in and out and germs setting up shop.

For months before reopening, Brunskill and other custodians around the district tested out various cleaning procedures and products.

One cleaning solution was good, but it went on sticky. Every surface they sprayed it onto, they then had to wipe it clean of residue, which wasn’t really practical in a school of 400 during a regular day.

Another product was bleach-based. It cleaned well, but put out its own chemicals into the environment and corroded metal slowly. That wasn’t going to work either.

Yet another erroneous trial came with a backpack and spray gun. Brunskill and company looked like the Ghostbusters, Smallwood said.

“It was kind of trial and error but there was science behind it,” Smallwood said.

Finally, after numerous tries, the district found its answer, with agreement from all schools—Bioesque, a clear, vaporous spray that shoots out of a refillable gun and dries quickly. It wouldn’t harm the students or the building, and it would kill coronavirus particles.

“If anything it’s made it better, taught us a lot about keeping the place sanitized,” Brunskill said.

PARENTING: 4 Questions You Should Ask Your Kids in 2022 to Understand Their Mental Health

(Almost) Back to Normal

In February 2021, Rogers reopened—at least halfway.

This was when COVID-19 numbers were back on the rise, thanks to spikes after the holidays.

In reopening, students were divided into two batches, or cohorts. One came in the morning. One came in the afternoon. (The rest of the day was spent online.)

Custodians cleaned in the intermission, during an hour and twenty minute break built into the schedule.

As an unspoken rule, custodians didn’t take long vacations or days off if they could help it. They became—if they weren’t already—the most valuable members on staff.

If one needed to be away for a day, he’d have to get someone to cover.

“We just did what we had to do to support it,” Brunskill said.

But as months have rolled by during the reopening process, the district has hit its marks and gradually relaxed restrictions, despite occasional hiccups.

A year after first reopening, for in-person instructions, Rogers is back in the swing of things. And not only are students happy to be back; so is the faculty.

“When the kids run by and they’re happy to be back—‘We’re here,’” Brunskill said, imitating children running by, “then you know you’re appreciated for sure.”

Brunskill isn’t just pleased to see the kids’ glowing faces back. He feels he’s learned something from it all—tightening ties on his team and improving building maintenance for the pandemic and beyond.

As much of the country has hailed essential frontline workers like Brunskill, Whitmer and other Michigan officials have endorsed a policy of hero pay, which would award essential in-person employees up to $2,000 for their contributions to society during the pandemic.

Brunskill already feels appreciated.

He’s still cleaning toilets, but that doesn’t bother him a bit. He’s the last barrier between school closures and in-person education, and everyone knows that as a Rogers mainstay, he’s defending his building well.

“If I wasn’t appreciated or needed or used, then this wouldn’t be happening,” Brunskill said. “I and the custodians are part of it.”

MICHIGAN SCHOOLS: ‘These Policies Do Attack Michigan Families’: Inside Betsy DeVos and the Michigan GOP’s War on Public Schools

Politics

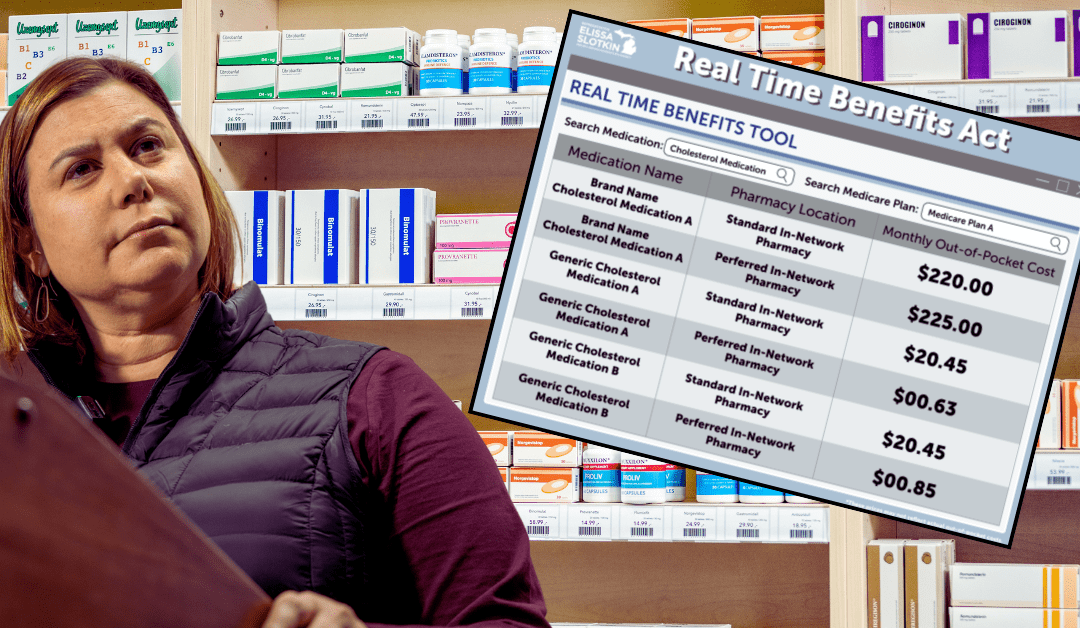

Slotkin urges Michiganders to compare prices before buying prescription drugs

A law sponsored by Congresswoman Elissa Slotkin is helping patients compare prices for different prescription drugs at different pharmacies—saving...

‘Melody’s Law’ would explicitly criminalize necrophilia in Michigan

BY ANNA LIZ NICHOLS, MICHIGAN ADVANCE MICHIGAN—There is no law on the books in Michigan that expressly criminalizes engaging in sexual conduct with...

SEIU workers ahead of NFL Draft: We are ‘the backbone of Detroit’

BY KEN COLEMAN, MICHIGAN ADVANCE MICHIGAN—A day ahead of the National Football League annual draft being held in Detroit, Service Employees...

Local News

4 Michigan dispensaries that will deliver weed straight to your doorstep

MICHIGAN—If you’ve ever dreamed of purchasing quality weed without ever having to leave your house, then you’re in luck. Michigan dispensaries have...

The 9 best pizzas in Michigan, according to our research

When it comes to finding the best pizza in Michigan, the options are endless. From the bustling city of Detroit to the quaint town of Cadillac,...