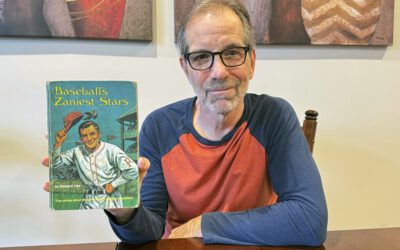

Jeneva Martinez of Roswell, NM, discusses a home renovation project with a landlord as a part of Rehab2Rental – a project designed by working-class people to loan money to small scale landlords to increase available rental units for Section 8 voucher holders. Photo by Gwen Frisbie-Fulton

I used to work in a daycare and I remember how the building would start to bustle with activity right at 5:30 p.m. As parents filed in, I’d dig through the toy bin for a lost mitten, Jackson’s exhausted-looking dad would admire his dozens of crayon drawings from the day, and Kaleigh’s mom would apologize again for leaving a lunch box in the room over the weekend, responsible for the ripe smell we had endured all day.

5:30 p.m. was a jumble of hats, gloves, coats, backpacks, prescription forms, take-home folders, envelopes stuffed with late fees, doctors’ notes about allergies. It was the transition hour for parents between work and home, maybe with a grocery run somehow squeezed between.

I remember one mom, the mother of a messy little 3-year-old whose braids were always pinned up with a rainbow of butterfly clips, saying to me: “I just don’t have room for even one more thing.”

Working-class people rarely do have time for one more thing.

Jobs, errands, home repairs. Children, elders, the grass is too long, the oil needs changing. Everything feels like a litany; an assault of needs and demands. There’s barely enough time to make dinner, let alone catch up with the neighbors. There’s no wiggle room in our schedules or our budgets; one more bill or flat tire could make everything come crashing down. No room for even one more thing.

Because I know the crush of being working class myself, this lack of time or room to breathe, I’m struck by how much recent work for social change is being led by working-class Americans.

The 2025 news cycle was dominated by discussions of high housing costs, massive budget cuts, and out-of-control inflation. We spent the year begging our elected leaders to do something. But it seems that regular, everyday people have both sounded the alarm and heralded the call.

It’s people like Jeneva Martinez and Nicole Scarpa in Roswell, New Mexico—busy moms who, tired of high housing prices, figured out a way to help local landlords fix up properties, increasing available rentals for Section 8 voucher holders. It’s people like Casey Tobias in Three Rivers, Michigan, who harnesses the goodwill of her neighbors to supplement the local government’s faltering safety net. Casey and her volunteers provide everything from food and laundry to rides for people released from the hospital so they can recover at home.

The meltdown of our infrastructure and systems is too big to ignore. Working-class people feel the urgency and witness the need firsthand every day. Michaela Mertz, in Chaves County, New Mexico, saw that her neighbors were relying on emergency medical services because they had no primary care doctor, so she started a volunteer EMS service, responding to community calls and providing free care. Jocelyn Smith, also in Chaves County, a single mom working at a radio station and facing cuts to her SNAP benefits, now collects and redistributes food to neighbors on her days off. Shante Woody, frustrated by the lack of opportunity in her neighborhood, created a weekly outdoor market in Greensboro, North Carolina, to help her neighbors showcase their side hustles.

Mandy Hodges was evicted from National Forest Service land outside Bend, Oregon, where she had been living in a camper for the better part of a decade, and is now leading local efforts to protect others living on public lands from the same fate. “No one has any place to go, you can’t just keep kicking people from town to town,” she says. “We’ve got to be the ones who do something.”

Having “no room for one more thing” and needing to be “the ones who do something” is the dichotomy working people exist in. For too long, working people have been relegated to the sidelines and excluded from positions of power. But a shift seems to be happening: Working-class people are taking the reins. From serving food in our communities to running for office, it’s clear that our knowledge and expertise are what America needs right now.

None of the working-class people I spoke to had room for one more thing—they are all as busy as you and I—but they’re stepping up and taking charge anyway. They know what’s wrong and have a good idea of how to fix it; they can’t and won’t wait around for the rest to catch up.

If you are looking for the heat in America in 2026, I say look at the people who have been forced closest to the fire. The ones who most risk being burned. That’s where you’ll find the movement.

You should know the names of these 9 activists from Michigan

Michigan has long been a hotbed for activism, from suffragists to abolitionists and LGBTQ+ advocates. Check out these nine powerful names you need...

In Walworth County, neighbors rallied for rides—and rediscovered what it means to be a community

When I was a new mom, I wanted nothing more than to move out into the countryside with my baby. I had been raised in mostly rural places and have...

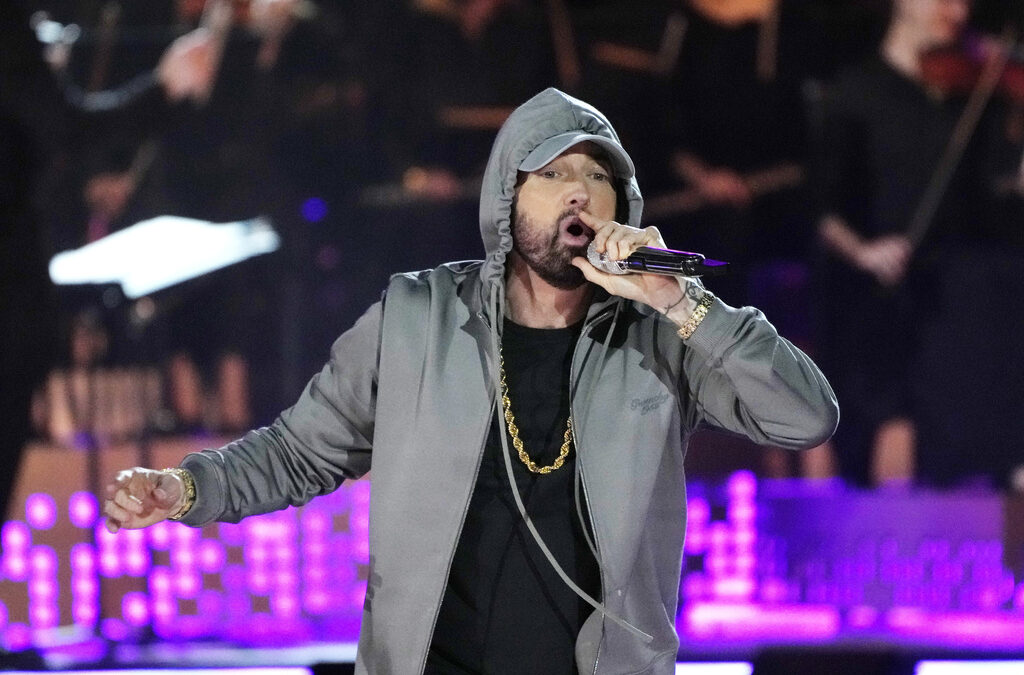

A former studio engineer is charged with stealing unreleased Eminem music and selling it online

A former Eminem studio engineer was charged Wednesday with stealing the Detroit rapper's unreleased music and selling it online, federal prosecutors...

Decorated pilot Harry Stewart, Jr., one of the last surviving Tuskegee Airmen, dies at 100

Retired Lt. Col. Harry Stewart Jr, a decorated World War II pilot who broke racial barriers as a Tuskegee Airmen and earned honors for his combat...

8 things you didn’t know about Flint native and pro boxer Claressa Shields

This fierce Michigander is a fighter in every sense of the word. Claressa Shields has fought her way to becoming a champion since she was a young...