Beer-battered cod is just the tip of the iceberg at this cultural and historic immersion.

DETROIT—The commotion captures the eye even before the sign does.

Families stream out of cars lining the blocks around the Sweetest Heart of Mary Church on Russell Street in Detroit, where a canvas banner spelling out “FISH FRY TODAY” sways in the wind. On this spring Friday, sunny but chilly still, an unusually spirited and mismatched crowd of suburban cars comes to the otherwise quiet and green neighborhood.

Fortunately, I’d been told to arrive a little bit before 3 p.m., when the fish fry officially opens to the public—so I beat most of the traffic. The church begins serving carry-out orders around the 3 p.m. mark, with the earlier requests mainly coming from parents picking their kids up from school, or nearby hospital workers whose shifts are ending. Usually, it’s not until 4 p.m. that this place really cranks into high gear.

Today, apparently, the crowd came early.

“The line has never been that long,” says Marianne Peggie, operations manager for the church, as she bolts up the wooden steps of the old brick convent that houses the dinner and snaps a photo.

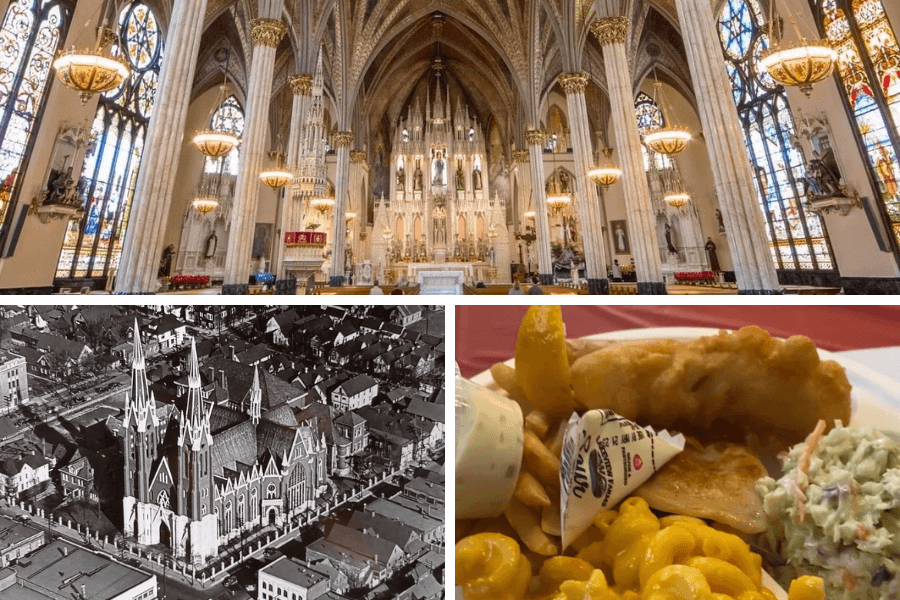

The line stretches out the doors of the convent-turned-parish-hall and toward the front steps of the city’s largest Roman Catholic church. Either word’s gotten around that this is one of the best Lenten fish fries in the city, or the lobster bisque special has really wound people up. Two things can be true at once.

I’m here for the religious tradition, the Detroit history lesson, and a tour of one of the most breathtaking churches in the state. But mainly, I’m here for the fish.

So let’s begin there.

When it’s an option, lake-caught perch is my go-to in Michigan. But at Sweetest Heart of Mary, local fish isn’t on the menu—leading me to choose between crab cakes, fried cod, baked cod, the aforementioned lobster bisque, or pierogies. As the crowd arrives, the kitchen decides for me—a plate of beer-battered cod it is, the truest measure of the sea legs of a kitchen.

Piled on my plate with a pierogi, lemon wedge, coleslaw, and fries, I snap a pretty picture. Then I nudge the pierogi out of the way and press the lemon between my thumb and forefinger to juice up the cod as much as I can.

As I take my first bite, I can’t help but think this is the quintessential fish-and-chips meal. The fish has that hard yet delicate shell on the outside, easily ruptured by a fork to reach the piping-hot, flaky soft flesh. It tastes like cod should—understated, yet still clearly of the sea.

(Later, it’s disputed whether the beer battering counts against my Lenten sacrifice of no alcohol during the week. After a brief discussion with folks who would know far better than I, it’s decided that the 4.5% alcohol from the lager has cooked off anyway.)

The church’s mac and cheese also catches me off guard. It’s homemade, actually, and the cheese strings from spiral to spiral. I’m a sucker for good mac and cheese—especially when it follows a crispy bite of fried fish.

It’s as I’m biting into this side that a gray-haired, spectacled man sitting at my table—there’s communal seating here—observes that I must be enjoying the day’s offerings, if my face is any indication.

Gary Vanassche is a long-time member of the congregation. He’s wearing a purple volunteer shirt, and has hunkered down with a plate before his shift begins.

Retired, Gary now has more time to spend with church activities, he says. So does his wife, Deanna, whom he proudly calls the “sparkplug” of the operation. Sure enough, Deanna joins us shortly thereafter with several updates on the line and the volunteers who showed up today.

Deanna grew up right around here in the Poletown neighborhood. She remembers how the street behind the church was lined with butchers and storefronts. It was always a mixed neighborhood—Black and white—with a lot of school children, Deanna said.

A picture on the second story of the parish hall illustrates Deanna’s vivid recollection. In black and white photography and from a bird’s eye view, you can see houses tucked in together and church steeples puncturing the sky. Even the church plot used to be different. Where there’s now a parking lot, there was once a school—such is Detroit.

Two turning points, Deanna said, ultimately drove the density—and most of the Poles—out of the neighborhood: First, the construction of I-75, which plunged a wide corridor through Poletown, taking down the homes and retail spaces in its way and opening the gates to suburbia. And second, the 1967 riots or rebellion—however you call it—which changed everything around here.

But on fish fry day, those events are mere memories and no longer the best dinner discussion—progress is being made. With volunteers working around the clock, the church stands tall as it did on that first midnight mass on Christmas Eve in 1893. And renovations completed by Ed Rourke—the same volunteer who’s the brains and hands behind the fried fish—have opened up a new banquet room in the parish hall to visitors.

And boy, is it full today.

“You have to really appreciate the outpouring of love that goes into this,” she says.

Sweetest Heart of Mary is one of the three churches along East Canfield Street built by Polish immigrants. The oldest is St. Albertus, recognizable by its one steeple. As a one-up, Sweetest Heart of Mary raised two. Just over the freeway, St. Josaphat—the newest of the trio—sends three steeples skyward.

Completed in time for a midnight Christmas mass in 1893—no small feat during the Panic of 1893, a depression that lasted until 1897—Sweetest Heart was the second church raised by Father Dominic Kolasinski. His first ground-up operation was St. Albertus, and the current church was dedicated in 1885. But soon after, the congregation splintered along the lines of the local parish and Kolasinski loyalists, so severely that a man was killed in the fracas. He was replaced by the local bishop, and along with his followers built Sweetest Heart (yes, with the two steeples) just outside the parish’s jurisdiction. Eventually, the Sweetest Heart family was welcomed back into the fold.

Today, the 130-year-old church stands in old glory, truthful to its age yet obviously nurtured with the constant upkeep by dozens of volunteers. Original walls peek through the narrow staircase up to the balcony, where the organ and choir are perched. From this vantage, the view can’t be beat—the enormity and detail of this place descend unto you all at once.

The showstopper is Sweetest Heart’s stained glass. Brought in as the church was built, the stained glass windows have weathered the century with small cracks and discolorations as scars. The panels give the biblical verses they depict color and animation, and one even portrays the heroism of Kolasinski, his face transposed onto that of Saint Michael.

Marianne—the church operations manager who discovered grandparents were married here—tells me that she’s looked into repairing the stained glass and is trying to raise what she can. The estimated cost would be more than $2 million.

As I mosey out of the church and back to my car, I meet Thom Mann—somewhat of a local celebrity here. Thom founded the Detroit Mass Mob, a movement with tens of thousands of followers that encourages Catholics to return to their ancestral churches of heritage.

“It always amazed me that our parents or our grandparents helped build these churches—I mean, they made major sacrifices,” Thom says. “And then when they left the city, they never came back. … I don’t know what it is about Americans. We tear down things and we build new.”

Nearby, walking with friends to her own car, Bernadette Pieczynski says she’s long been meaning to visit Sweetest Heart. The fish fry was a perfect excuse to travel over from the east side.

I ask her what she thought about the fish, and she says she liked it. But more than that, she came away with a new tie to Detroit’s Polish community, both past and present.

“Being of Polish heritage,” she says, “it means a lot to know how these people came with nothing. They came and built this gorgeous, beautiful church.”

Several years ago, TV commercials with the catchphrase “Catholics Come Home” caught my eye. I always thought it was a perfect nutshell of savvy marketing—three words that can call to a lifetime of religious and cultural deliberation.

Being here shows that that expression is actually quite organic, to more people than just me.

I grew up in the Catholic Church and grew away with age. But I still feel a magnetic draw to the steeples and bells. For me, it’s not a beckoning of religiosity—for the most part, anyway. It’s that cultural calling we all feel in some way to connect more deeply with the life, values, and practices of ancestors.

So, today, I guess that’s where the fried fish comes into play. Yes, it’s part of a sacrifice, a reminder that our personal desires are nothing compared to the greater good. But its greatest value more so is in bringing people together—whether they’re here to support the parish, to discover their history, or because they saw a sign outside proclaiming “FISH FRY TODAY” and decided that sounded pretty darn good.

As Deanna told me, “We have people coming from all over. It’s really a big conglomeration.”

VIDEO: Trump isn’t the only republican facing charges for alleged financial crimes

https://www.tiktok.com/@gandernewsroom/video/7361494909938978090 A whole lot of Michigan Republicans and lobbyists are facing criminal charges for...

VIDEO: It’s expensive to be poor in Michigan

https://www.tiktok.com/@gandernewsroom/video/7361154790300060974 Ever heard of predatory payday loans? Here’s how new laws could help protect...

Here’s everything you need to know about this month’s Mercury retrograde

Does everything in your life feel a little more chaotic than usual? Or do you feel like misunderstandings are cropping up more frequently than they...

The ’Gander wins multiple 2023 Michigan Press Association awards

MICHIGAN—The ’Gander Newsroom has earned multiple awards in the 2023 Michigan Press Association Better Newspaper Contest. The awards were announced...

Michigan Republicans ask Supreme Court to restrict medication abortion access

A lawsuit supported by Republicans could disrupt access to the most common form of abortion—even in Michigan, where reproductive rights are...