Legal battles have complicated efforts to shut down an oil pipeline beneath the Straits of Mackinac. But a recent ruling from a judge could mark the start of the final chapter in the years-long saga.

MICHIGAN—Each day, nearly 23 million gallons of oil rushes through a 70-year-old steel pipeline beneath the Straits of Mackinac that stretches about 645 miles across Michigan.

Line 5, as the pipeline is called, is part of Enbridge’s 8,600-mile Lakehead System which transports light crude oil and natural gas liquids across the midwest and Canada. And despite insistence from Enbridge executives that Line 5 has “operated without incident” since 1953, reports show the pipeline has spilled at least 1.1 million gallons of oil in the past 50 years.

For decades, state and tribal leaders have been sounding alarm bells over the devastating consequences that more leaks would have on the Great Lakes and its surrounding waterways. But years of litigation across multiple states have done nothing to stop the flow of oil and gas.

Now the case could soon be headed back to a Michigan courtroom—and state Attorney General Dana Nessel may finally find herself in a position to have the pipeline shut down for good.

Here’s the Deal:

In 1953, the state of Michigan signed an easement agreement that allowed Line 5 to be constructed beneath the Straits of Mackinac in exchange for a one-time payment of $2,450. The pipeline has been in operation by different companies ever since—and now, under Enbridge, it reportedly transports the natural gas used to supply about 55% of Michigan’s propane needs.

Much of the natural gas that runs through the Straits of Mackinac ends up refined into propane and is used in the Upper Peninsula, while much of the crude oil is processed at oil refineries in Detroit and Toledo. The remaining fuel crosses the St. Clair River for processing in Ontario.

(Courtesy/Oil & Water Don’t Mix)

Since 1968, Line 5 is estimated to have spilled at least 1.13 million gallons of oil and natural gas liquids across 33 different incidents—most recently in 2015. The largest spill came in 1999 when a leak of more than 220,000 gallons of crude oil forced hundreds to evacuate Crystal Falls.

In 2018, a tugboat anchor ripped its way through several inches of steel cables and caused significant damage to a stretch of the underwater pipeline—reigniting fears over the consequences of a possible pipeline rupture and oil spill in the Great Lakes.

In the final months of Rick Snyder’s tenure as governor, his administration signed off on plans to authorize Enbridge to build a protective tunnel around the pipeline—but Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s administration quickly put the kibosh on the plans when she took office in 2019, with a formal opinion from Nessel that found the agreement unconstitutional and unenforceable.

Shortly after taking office, Nessel also took Enbridge to court to argue that a 4.5-mile stretch of the Line 5 pipeline beneath the Straits of Mackinac should be decommissioned altogether—namely because the anchor strike had exacerbated the risk of a potential oil spill.

And in 2020, Whitmer formally revoked the 1953 easement agreement with Enbridge in the Straits of Mackinac and ordered the Canadian company to shut down the pipeline by May 2021.

But two years of subsequent litigation between the state and Enbridge has stalled its closure.

Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel speaks during a news conference in Flint. (Jake May/The Flint Journal via AP, File)

In Nessel’s lawsuit, she argued the continued operation of Line 5 represented a violation of the state’s public trust doctrine and the Environmental Protection Act because the pipeline was “likely to cause pollution, impairment, and destruction of water and other natural resources.”

“I have consistently stated that Enbridge’s pipelines in the Straits need to be shut down as soon as possible because they present an unacceptable risk to the Great Lakes,” Nessel said in a statement announcing the lawsuit against Enbridge. “We were extraordinarily lucky that we did not experience a complete rupture of Line 5 because, if we did, we would be cleaning up the Great Lakes and our shorelines for the rest of our lives, and the lives of our children as well.”

That case dragged on for more than a year until the summer of 2020, when a state court ordered that the pipeline needed to be shut down for several weeks to ensure its safety. Michigan and Enbridge then both filed motions asking the state court to decide the case, but Enbridge changed course and instead asked for the case to be heard in a federal courtroom.

Last year, a federal court denied Nessel’s request to send the case back to a state court—prompting Nessel to file an appeal, which had asked the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals to make the final decision on whether the case should be heard in state or federal courtroom.

The Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals granted Nessel’s request to take up the case last week. A panel of judges will soon decide in which courtroom the original litigation can proceed. Nessel wants to keep the case in Michigan; Enbridge prefers the case be decided by a federal judge.

And at the conclusion of the litigation, both sides will finally be able to make arguments about whether the pipeline should actually be shut down, rather than where the case should be heard.

“It is a Michigan case that belongs in a Michigan court,” Nessel said in a statement. “Enbridge voluntarily litigated this case in state court for over a year before deciding it would prefer a different forum. I am hopeful that they will send this case back to state court where it belongs.”

Another Legal Battle in Wisconsin

The disastrous potential consequences of an oil leak from Line 5 isn’t limited to Michigan.

When the pipeline was constructed in the early 1950s, a 12-mile stretch was also laid through the middle of a reservation for the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians in Wisconsin. It crossed more than 40 local rivers and streams, including the Bad River itself.

(Courtesy/Enbridge)

An easement agreement with Enbridge that allowed the operation of the pipeline through tribal land expired in 2013. But just like in Michigan, Enbridge did nothing to stop the flow of crude oil—even after the tribe issued a resolution to have the pipeline decommissioned in 2017.

In 2019, the tribe’s frustrations with Enbridge boiled over into a federal lawsuit. More than three years passed before the case led to a trial last October. And last month, there was a verdict.

The judge’s ruling found that Enbridge was consciously trespassing on the reservation by continuing to operate the pipeline, and that Line 5 posed a “public nuisance” because an oil spill would pose an imminent threat to the environment and could create catastrophic damage.

The ruling ordered Enbridge to pay about $7 million to compensate the tribe for a decade of trespassing, and it also set a clear date for Enbridge to shut down the pipeline: June 16, 2026.

Attorneys for the tribe said the order marks the first time they’ve been able to receive a finite shutdown order for the pipeline—but three years is still “too long” to wait, and $7 million is “a slap on the wrist” for Enbridge, which makes an estimated $1.5 million daily from the pipeline.

Appeals from both sides are expected to play out over the coming months, which are likely to lead to continued legal delays in actually having the pipeline decommissioned in Wisconsin.

“This case has never been about money, but restitution awards are extremely important for deterring other trespasses,” said Riyaz Kanji, an attorney representing the Bad River Band.

More Regulatory Solutions

Amid the ongoing legal battles in Michigan and Wisconsin, state regulators in Michigan are poised to make some significant decisions that could impact the future of the Line 5 pipeline.

The Michigan Public Service Commission is set to decide this year on a permit that would essentially allow Enbridge to replace and relocate a stretch of Line 5 beneath the Straits—swapping out the dual-pipeline with a single steel pipeline buried in a tunnel.

(Courtesy/Michigan Public Service Commission)

Those proceedings were initially closed last March, but last summer the commission decided to reopen the case for additional hearings to gather feedback from local stakeholders. Those proceedings were again closed in May, and a decision on the permit could be issued anytime.

The next commission meeting is scheduled for Aug. 30.

Environmental activists and tribal leaders have spoken out against the project in recent months—arguing that a leak in the tunnel could cause the tunnel to be filled with crude oil and natural gas liquids, potentially leading to a catastrophic explosion from a single spark.

Should the commission approve the project, it will also face a review from the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy (EGLE) and the US Army Corps of Engineers, which would reportedly delay construction of the tunnel until at least 2026.

Federal Solutions

Beyond the ongoing litigation and regulatory approvals, proponents of shutting down the Line 5 pipeline have also urged President Joe Biden’s administration to take action to ensure the Great Lakes are protected. Officials at Oil and Water Don’t Mix have requested Biden revoke the presidential permit that allows Enbridge to operate Line 5 and order the Department of Justice to intervene on Michigan’s behalf in the ongoing lawsuits between Michigan and Enbridge.

The group is also encouraging Michiganders to reach out to the White House directly.

For the latest Michigan news, follow The ‘Gander on Twitter.

Follow Political Correspondent Kyle Kaminski here.

Politics

Trump says he would allow red states to track pregnancies, prosecute abortion ban violators

In an interview published by Time magazine this week, former president Donald Trump detailed his plans for a potential second term and said he would...

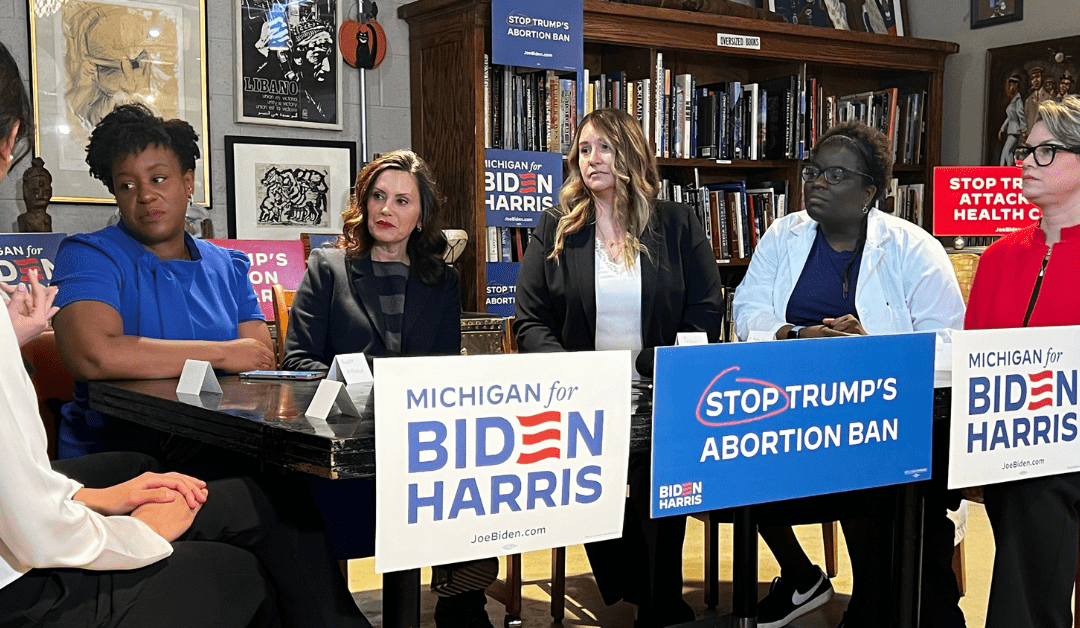

Whitmer: Reproductive rights still ‘in jeopardy’ in Michigan

Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer is urging Michiganders to re-elect President Joe Biden in November—or else risk losing access to reproductive...

How to apply for a job in the American Climate Corps

The Biden administration announced its plans to expand its New Deal-style American Climate Corps (ACC) green jobs training program last week. ...

Local News

Detroit date night done right: 12 fresh and exciting ideas

Whether you want to make a good first impression with your latest Bumble match or surprise your spouse with an exciting evening out, Detroit is full...

Black cowboy culture will be on full display at upcoming Flint rodeo

Flint, Michigan, is set to host an exciting and culturally significant event this June: the Midwest Invitational Rodeo. This eagerly anticipated...