Almost two million Michiganders live in rural communities. Meet the people bringing health care to their towns.

It’s no secret that Michigan’s rural communities need help connecting residents with health care. Staffing shortages around the state have forced some Michigan hospitals to consolidate or close altogether, and provider burnout is at an all-time high.

Yet 20% of Michiganders live in rural areas, where health care needs are just as diverse as those in urban regions of the state.

“Rural folks have worse health outcomes for a number of reasons. You have to ask why,” said Eneka Lamb, a third-year medical student at Michigan State University’s College of Human Medicine. “There’s nothing inherently different about a person living in a rural community. So why are they dying at higher rates? Access is one reason, and then the care that you get when you reach a facility is another issue.”

Eneka is part of a unique program here in Michigan, called the Leadership in Rural Medicine Program (LRM). It’s been training medical students to serve underserved rural communities across the state for nearly 50 years.

“Typical medical school training usually happens in urban areas where that’s a lot of support,” said LRM program director, Dr. Andrea Wendling “If you only train in an urban area, you know how to practice with a lot of support—you have a cardiac team, a pulmonology team, etcetera. If you then go to a rural hospital that doesn’t have that support, you can be really uncomfortable in those settings.”

The LRM program first started in the 1970s as a way to combat the shortage of rural physicians in Michigan—making it one of the first rural training programs in the nation, according to Wendling.

“The students who train in the [Leadership in Rural Medicine program] are more likely to go into primary care and they’re most likely to go into high need rural specialties,” she said.

Growing up, Eneka Lamb never envisioned herself pursuing a career in medicine. She became familiar with issues related to global health as an American expat growing up in Hong Kong, but had never considered it as a potential career path, she said.

“I don’t have one of those stories where I wanted to be a doctor as a kid or anything,” Lamb said.

However, her perspective changed during her time as an undergraduate student at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, where she became interested in maternal and child health in vulnerable populations.

Lamb said that the power dynamics that women and children face—financially, politically, and legally—can take a toll on physical health. By taking what she calls a “bio-psychosocial approach” to health, Lamb connected with mentors at Duke who helped her lean into her research interests.

“I could make an argument for anything being related to somebody’s health,” she said. Through her research, she focused that broad idea onto vulnerable women and children—and graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Global Perspectives of Maternal & Child Health.

Wanting to do more to help women in underserved communities, Lamb then signed up for the Peace Corps. She was assigned to a small, Indigenous village in the middle of a rainforest in Guyana, where she would live and work for the next three-and-a-half years.

During her time in the village, Lamb learned the importance of patients understanding their rights—and how she could advocate for them. The most eye-opening experience, she said, was witnessing the numerous health disparities that Indigenous members of the community faced.

“The health outcomes of my community members in Guyana—and many, many communities in the US—who are Indigenous or native are horrific. They have very poor health outcomes, and I’d just never been exposed to that before,” she said.

Lamb learned the need to truly integrate with the community she had arrived in, rather than simply serving the people there. While her desire to help came from a good place, the tight-knit village community was hesitant to welcome her with open arms.

“When I first moved to the village, people were very friendly, but nobody told me their name. They were like, ‘Oh, you can call me auntie’ or ‘call me nurse,’” said Lamb.

Over the course of six months, the community began to warm up to Lamb—eventually trusting her with their names. After living in the community for years, Lamb brought up these interactions with hospital staff and was surprised by what they told her.

“They said that they didn’t think I would stay for as long as I did. They said, ‘Why would we tell you something so personal if you were just going to leave?’ So it just really taught me a lesson about building trust, and I think that’s really important in any community that you go to,” said Lamb.

Eneka Lamb/MSU College of Human Medicine

Here in Michigan, that’s part of the LRM program, said Wendling.

“We try to get our students engaged in the community and help them understand how care is networked and delivered,” she said. “They meet with hospital leadership so they understand what keeps them up at night, the director of public health for the region, they even meet with the chamber of commerce so they can see where the people in their community live, work, and go to school.”

After students spend the first two years of the program learning skills at MSU’s College of Human Medicine, they relocate to their pre-matriculation designated rural campus in Midland, Traverse City, or Marquette—areas of the state that, not coincidentally, overlap with Michigan’s maternity deserts. Once they’ve relocated, students work with local hospitals and alongside health care providers in a variety of specialties.

To ensure that students get the skills they need to be able to successfully practice in rural areas, the LRM program includes hands-on clinical training as well as wilderness medicine, leadership, public health, and community service opportunities in rural counties around Michigan. Students take part in a variety of clinical experiences in small and large rural hospitals, outpatient clinics, and emergency settings.

The program is a bright spot in Michigan’s health care provider crisis.

“When we look at our workforce study for our rural training program, 53% of students ended up practicing in Michigan for their career,” Wendling said.

Other programs have also been designed in recent years, to help with Michigan’s rural health care needs. In 2023, Central Michigan University launched a Rural Health Equity Institute, to focus on rural health priorities and opportunities to improve access to services like telemedicine.

State government has also gotten involved. MiREACH—the Michigan Rural Enhanced Access to Careers in Healthcare program—funds on-the-job education and services, tuition, clothing, supplies, mileage reimbursement, and more for Michiganders who want to start or grow their career in rural health care.

While smart tactics like telemedicine have helped rural Michiganders connect with health care providers, the shortage of primary care specialists—like OBs and family medicine physicians—is not something that can be ignored.

“I think that women’s choices are limited [in rural areas] in ways that they’re not limited in urban communities in our state,” Wendling said.

“We need to look at the way that we’re training people in our country, we need to look at who we’re recruiting, and we need to look at how we’re supporting STEM classes in rural communities. We need to do better in order to not let disparities like this continue.”

Politics

SEIU workers ahead of NFL Draft: We are ‘the backbone of Detroit’

BY KEN COLEMAN, MICHIGAN ADVANCE MICHIGAN—A day ahead of the National Football League annual draft being held in Detroit, Service Employees...

Investigator says Trump, allies were uncharged co-conspirators in plot to overturn Michigan election

DETROIT—A state investigator testified Wednesday that he considers former President Donald Trump and his White House chief of staff to be uncharged...

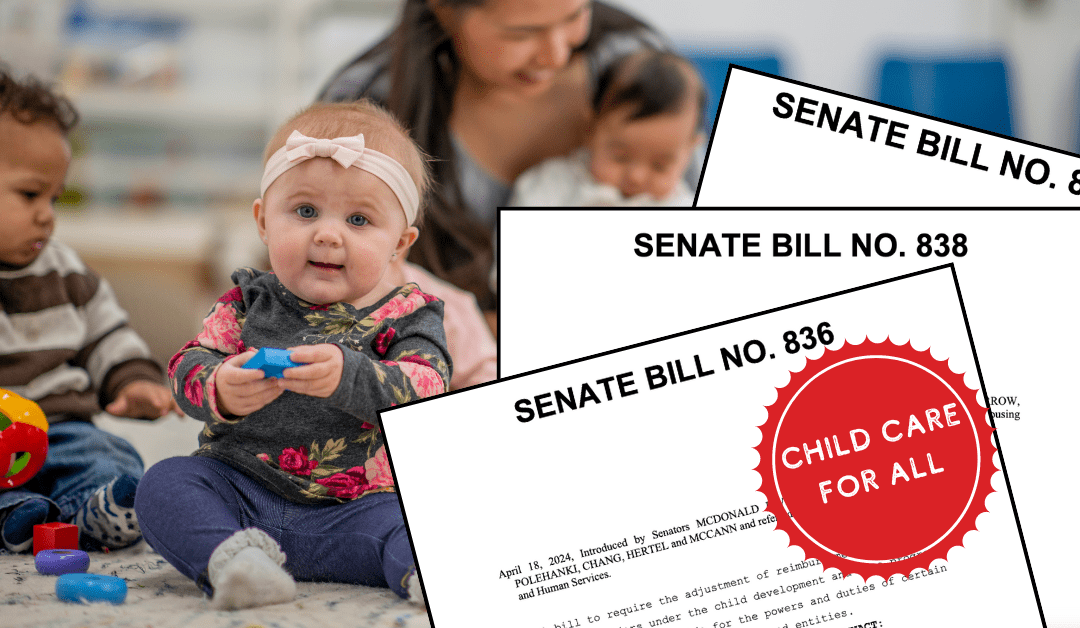

Michigan Dems introduce ‘Child Care for All’ legislation to lower costs for families

Lawmakers say Michigan is facing a ‘child care crisis.’ But a series of bills introduced this month would help to make child care (much) more...

Local News

The 10 best burger joints in and around Lansing

Warning: Do not read this list if you missed lunch or you will find yourself hopping in the car to drive to these best burger joints in Lansing. ...

10 unique wedding venues in Michigan to suit every kind of couple

From a distillery in Detroit to a summer camp, we’ve rounded up some of Michigan’s most unique wedding venues. Of all the elements you need to...