BY KYLE DAVIDSON, MICHIGAN ADVANCE

MICHIGAN—There are 290 concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) in the state of Michigan whose livestock generate 62.7 million pounds of waste daily. As the state continues to battle environmental concerns like harmful algal blooms and E.Coli pollution, the Environmental Law and Policy Center (ELPC) is calling for stricter regulations and enforcement to ensure these operations are held responsible for pollution.

The complete report is available on the Environmental Law and Policy Center’s website.

In a report published earlier this month, the ELPC examines how concentrated animal feeding operations are polluting Michigan water, reviews the regulations imposed on these operations, and offers recommendations for reducing pollution at these operations.

Michigan law defines an animal feeding operation as a lot or facility where the animals will be stabled or confined and fed or maintained a total of 45 or more in any 12-month period. A large concentrated animal feeding operation is an operation with a minimum number of animals including 700 dairy cows; 1,000 cattle; 2,500 swine over 55 pounds; 125,000 chickens and/or discharges pollutants from its production area.

The report notes that industrialization in agriculture has been growing over the past 50 years with concentrated animal feeding operations growing to dominate livestock production. Since 1987, Michigan has gained 91,804 dairy cows while losing 5,018 dairy farms, gaining 1.78 million hogs while losing 3,298 hog farms over the same period.

As of 2012, concentrated animal feeding operations generated more than 20 times the amount of fecal wet mass produced by all of the nation’s humans. In Michigan, permitted large scale feeding operations produced more than 17 million more pounds a day than the state’s 10 million person population, the report said.

Many dairy and hog feeding operations use liquid manure systems and store untreated waste in liquid form in “lagoons” which third parties later apply to crop fields as fertilizer. However, hauling this liquid waste is costly, with hauling costs often exceeding the value of fertilizer when hauled further than a mile, which often leads to the application of more nutrients to nearby fields than crops need. The report also notes that this waste often contains components that are either harmful or carry no benefit, such as wastewater runoff, detergents, antibiotics, PFAS and pathogens including E. coli.

“The reality is that the primary goal of CAFO waste spreading is waste disposal, not crop fertilization. CAFOs gain a significant economic advantage by concentrating their industrial production and offloading their waste in this way. This comes at the expense not only of smaller family-scale farmers, but also the environment,” the report says.

The excess nutrients and E. coli present in this waste are considered the two largest threats to water quality and human health. Excess nutrients like phosphorus can cause harmful algal blooms when overapplication or misapplications leads to nutrient loss in water.

These harmful algal blooms generate toxins which have been linked to kidney and liver damage, gastrointestinal issues, infections, dementia, amnesia, neurological damage and death. They also deplete dissolved oxygen levels in water, supporting the growth of toxic organisms and causing major fish die-offs.

According to the report, the cyanotoxins generated by these harmful algal blooms are not subject to regulation under the federal safe drinking water act, or under state policy. While the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) has a mapping tool to track cyanobacteria blooms, this program relies on citizen reporting rather than systematic water testing.

Additionally, nitrates, another excess nutrient found in feeding operation waste, pose a risk to groundwater. These nutrients can hinder the ability of blood to carry oxygen and have been linked to birth defects, miscarriage, blue baby syndrome and cancer.

E.Coli is also a major concern from feeding operation waste. This bacteria, which lives in the intestines of warm-blooded animals, can cause diarrhea; stomach cramping, pain or tenderness; nausea and vomiting, with older adults and younger children at a greater risk for developing a life threatening form of kidney failure from infection. The report notes that partial body contact with water exhibiting higher levels of E. Coli can lead to infection, while total body contact can cause gastroenteritis, cryptosporidiosis, cholera, and other intestinal parasites.

The report said CAFOs place a significant burden on water usage, with agriculture using 70% of freshwater worldwide.

Additionally, these operations have been tied to other harms, including the transmission of diseases, creating antibiotic resistant bacteria, transporting PFAS, air pollution and climate impacts, the report said.

It also points to a number of negative social impacts of factory farming, including loss of tourism dollars, reduced property values, increased drinking water treatment costs, as well as concerns over animal welfare, workplace safety and a lack of adequate farmworker housing.

While state law carries provisions specifically for regulating concentrated animal feeding operations, the reporter argues these operations “are not regulated like the industrial polluters that they are.”

As part of their permitting requirements, large scale feeding operations must develop and follow a comprehensive nutrient management plan which at minimum includes adequate storage, best management practices for controlling runoff, protocols for soil and waste testing and recordkeeping requirements among other things. New permits are issued every five years.

According to the report, the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy’s (EGLE) draft permit for 2020 included a number of key provisions that had been missing since the first general permit was issued in 2005. This included prohibiting winter waste application, requiring the use of a phosphorus risk assessment tool called the MPRA, and partially closing a loophole for waste that is sold to third parties.

“The 2020 Draft Permit still came far short of assuring compliance with water quality standards, but it was an important step in the right direction,” the report said.

However, EGLE later abandoned many key provisions in the draft after facing pressure from the concentrated animal feeding operation industry, the ELPC said. Despite these concessions, the industry challenged the final 2020 on both the administrative level and in court. The case currently sits before the Michigan Supreme Court after the Michigan Court of Appeals ruled in the industry’s favor holding that the 2020 permit terms were “unpromulgated rules” that should have been issued pursuant to formal rulemaking procedures.

However, the ELPC notes that EGLE has lacked the authority to promulgate new rules since 2006, with this ruling seemingly barring EGLE from strengthening the requirements of any of its environmental permits.

Alongside the permitting challenge, ELPC also pointed to other concerns in how large-scale feeding operations are regulated, noting that they are not required to treat their waste and are only required to comply with best management practices, rather than numeric pollutant limitations.

The ELPC argues that these practices have little impact in addressing pollution from tile drainage, in which contaminants from feeding operation waste spread on fields flow through drain tiles and are inevitably discharged into surface waters. In some instances, these practices can worsen tile-related pollution.

According to the ELPC, concentrated animal feeding operations are also permitted to transfer their untreated waste to third parties who can dispose of it without direct regulatory oversight.

Compared to the treatment of human sewage, which can be treated and land applied as biosolids, waste from large-scale feeding operations faces a significantly lower waste disposal standard, the report says.

The ELPC also argues that Right to Farm Laws limit communities and neighbors from taking action against contamination by providing agricultural operation immunity against nuisance lawsuits provided they comply with Michigan’s Generally Accepted Agricultural Management Practices. These laws also bar local governments from passing ordinances that conflict or overlap with the Generally Accepted Agricultural Management Practices.

In order to reduce pollution from concentrated animal feeding operations, the ELPC outlined a number of policy recommendations in the final sections of its report.

These recommendations include creating a statewide total maximum daily load for dissolved reactive phosphorus, total phosphorus and nitrates/nitrites, dictating the maximum amount of these pollutants that can enter a body of water so that the body may continue to meet water quality standards.

It also recommended a number of steps to strengthen EGLE’s permitting for Concentrated Animal Farming Operations, with many of these recommendations centered around addressing pollution from tile drain systems.

The ELPC also recommended stricter enforcement of these permits, asking for EGLE to escalate and close out unresolved enforcement actions; conduct more unannounced audits and inspections; impose stricter consequences on repeat offenders, including suspending their permits; and reinstating anonymous citizen reporting of potential pollution discharges, among other recommendations.

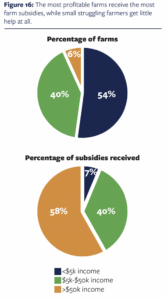

The report argued that the incentives concentrated animal feeding operations receive for complying with voluntary best management practices for pollution clean up alongside subsidies for waste management projects and compliance with regulations allows these companies to externalize their costs onto taxpayers and the environment, while receiving a disproportionate share of funds compared to smaller operations. In its recommendation, the ELPC argues the state either needs to radically redesign its voluntary incentive programs, or scrap them altogether.

Additionally the report recommends investments to expand the state’s water monitoring program, and to support family farmers who use sustainable regenerative agriculture practices.

It also recommends stricter regulations of anaerobic digesters, which creates biogas for energy generation by breaking down organic material such as manure, food waste, and other organic waste. The digestate produced alongside the biogas in these facilities is often placed into lagoons and applied to land as fertilizer.

The ELPC argues these facilities are regulated in much of the same way as concentrated animal feeding operations, and calls on the state to subject digestate to the land application requirements that are at least as strict as the standards for biosolids, and ensure these digesters carry appropriate air quality permits.

This coverage was republished from Michigan Advance pursuant to a Creative Commons license.

Fresh food, stronger farms: Michigan invests millions to support local agriculture

A new ‘Farm-to-Family’ grant program aims to connect Michigan farmers with more consumers, boost local economies, and build a stronger food system....

Rooted in Tradition: How Michigan’s Christmas tree industry is keeping the holiday spirit alive

Family farms—and traditions—help Michigan produce more Christmas trees than almost every other state in the country. GOBLES—Under a clear December...

How Gen-Z is helping rural Michiganders turn out to vote in the UP

Michigan is one of several critical swing states in this year’s election, and for Carly Sandstrom, a Marquette native and canvasser with the...

3 rural communities in Michigan got remote blood pressure care—and the results were dramatic

A pilot program helping rural Michiganders monitor their blood pressure led to big improvements—could this be what finally helps bring down the rate...

Report: Project 2025 would ‘devastate’ Michigan’s rural communities

Republicans’ Project 2025 agenda aims to enact a far-right agenda that would hurt all Michiganders, especially those living in rural communities,...