Students learning about vernal pools. Photo courtesy of Brandon Schroeder via Michigan Vernal Pools Partnership

Vernal pools are a critical part of Michigan’s natural ecosystem—but they’re not protected by state regulations. Here’s how Michiganders are helping.

Imagine you’re out hiking in the woods. It’s a fresh spring day—the air is still damp with the end of winter, and the ground’s a little soggy from recently melted snow. You pass a tree and see something—a small, shallow pool of water. You chalk it up to the snow melt and keep on your way.

What you’ve just passed is a vernal pool—one of Michigan’s rarest bodies of freshwater. And it’s absolutely critical to the future of our forests, lakes, and farmland.

On a recent Sunday afternoon in Okemos, dozens of nature lovers gathered at the Michigan Nature Association to join the Vernal Pool Patrol—a group of volunteers across the Mitten who act as citizen scientists, looking for vernal pools near them and collecting data to send to the Michigan Natural Features Inventory (MNFI). So far, community members and scientists have mapped around 900 vernal pools in Michigan. But there are still about 4,400 to go.

“Part of the reason we started the Vernal Pool Patrol is because we realized that there’s not much information out there about where these vernal pools are,” said Yu Man Lee, a herpetologist—someone who studies reptiles and amphibians—with the MNFI.

To be part of the Vernal Pool Patrol means you need to be something of a nature sleuth. “Vernal” means spring, and vernal pools are formed when the snow melts. By summer, they usually dry up. But when they’re here, they’re so important that they’ve been called the “coral reefs of Northeastern forests.”

“You can hear when you walk up to [a vernal pool] because it’s full of wood frogs,” said Abigail Pointer, the Michigan Nature Association’s vernal pools partnership coordinator.

The frogs are there because it’s a safe haven for them to rest, eat, and reproduce. Having a fishless habitat is important to the life cycle of many of Michigan’s creatures, like fairy shrimp, spotted salamanders, and in some areas, turtles.

“They’re a great place for animals to seek shelter and find food,” Pointer said.

In addition to being a breeding and feeding ground for animals and insects—including rare, threatened, and endangered species—vernal pools help reduce flooding and erosion by catching runoff and trapping water and sediments. By constantly filling up in the spring and drying up in the fall, these small bodies of water also help cycle nutrients throughout the ecosystem.

A problem vernal pools currently face is that they’re not well protected under Michigan’s wetland laws and regulations, which only apply to wetlands that are five acres or more in size.

“Because they’re so small, vernal pools don’t [usually] meet these criteria,” said Lee, the herpetologist.

That means construction, development, and the effects of local and global extreme weather can have serious impacts on vernal pools—and the ecosystems they’re part of.

How can Michiganders help?

Any Michigander can become a Vernal Pool Patroller, from any generation.

“We’ve done some work with educators and teachers in schools that are now participating in the program,” Lee said. “We work with students who are in middle school and high school and teach them the protocol necessary to collect accurate data. We’ve even had second graders out to explore a vernal pool with us.”

At the Okemos event, younger attendees gathered at tables to color black-and-white pictures of Michigan wildlife with crayons. Matching games interested elementary and middle school kids, testing their knowledge by identifying macroinvertebrates—animals or insects that don’t have a backbone, like crustaceans or worms—that can be found in ecosystems throughout Michigan forests. Handouts with pictures of invasive plant species were distributed by volunteers, while many older Michiganders took interest in the tri-fold, educational poster boards lining the welcoming halls.

“It’s cool that it seems like no matter the age, there seems to be this innate interest in science for folks,” Lee said. “In just a couple scoops with a net from the pools and stuff, you’re able to see species like fairy shrimp, which you never see anywhere.”

To find one near you, visit the Michigan Vernal Pools Database. To get involved in protecting vernal pools, the Michigan Vernal Pools Partnership has a helpful toolkit for advocates and nature lovers in communities. If you’re an educator, a parent, or a grandparent who wants to teach Michigan’s youngest generations about vernal pools, here’s a guide. And if you just want to see awesome photos of what volunteers have found in our state’s vernal pools, head to this photo gallery.

Politics

Trump says he would allow red states to track pregnancies, prosecute abortion ban violators

In an interview published by Time magazine this week, former president Donald Trump detailed his plans for a potential second term and said he would...

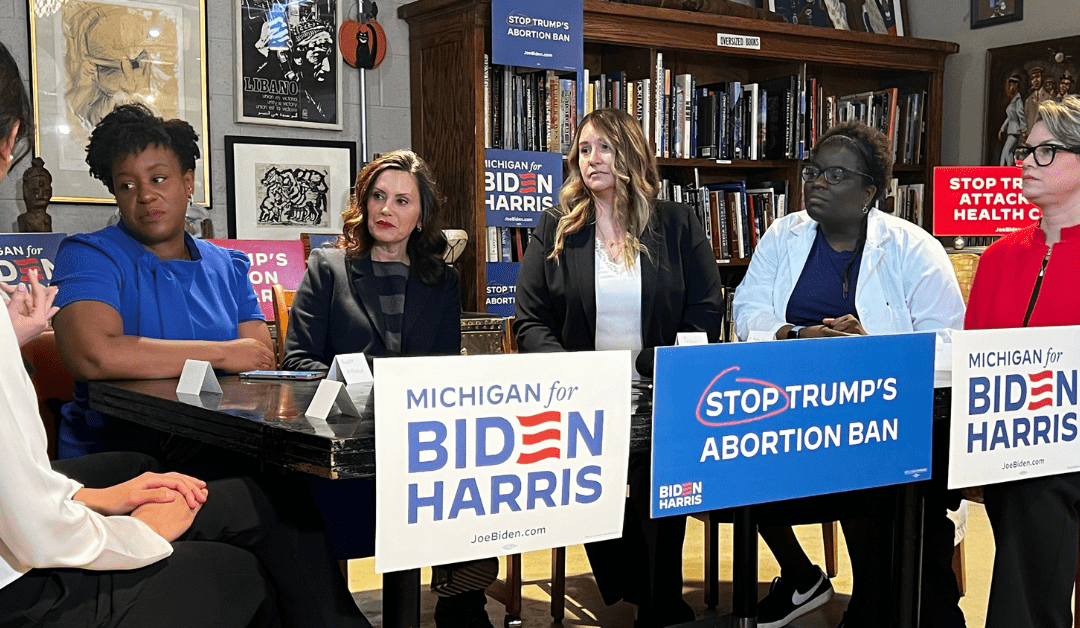

Whitmer: Reproductive rights still ‘in jeopardy’ in Michigan

Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer is urging Michiganders to re-elect President Joe Biden in November—or else risk losing access to reproductive...

How to apply for a job in the American Climate Corps

The Biden administration announced its plans to expand its New Deal-style American Climate Corps (ACC) green jobs training program last week. ...

Local News

Detroit date night done right: 12 fresh and exciting ideas

Whether you want to make a good first impression with your latest Bumble match or surprise your spouse with an exciting evening out, Detroit is full...

Black cowboy culture will be on full display at upcoming Flint rodeo

Flint, Michigan, is set to host an exciting and culturally significant event this June: the Midwest Invitational Rodeo. This eagerly anticipated...