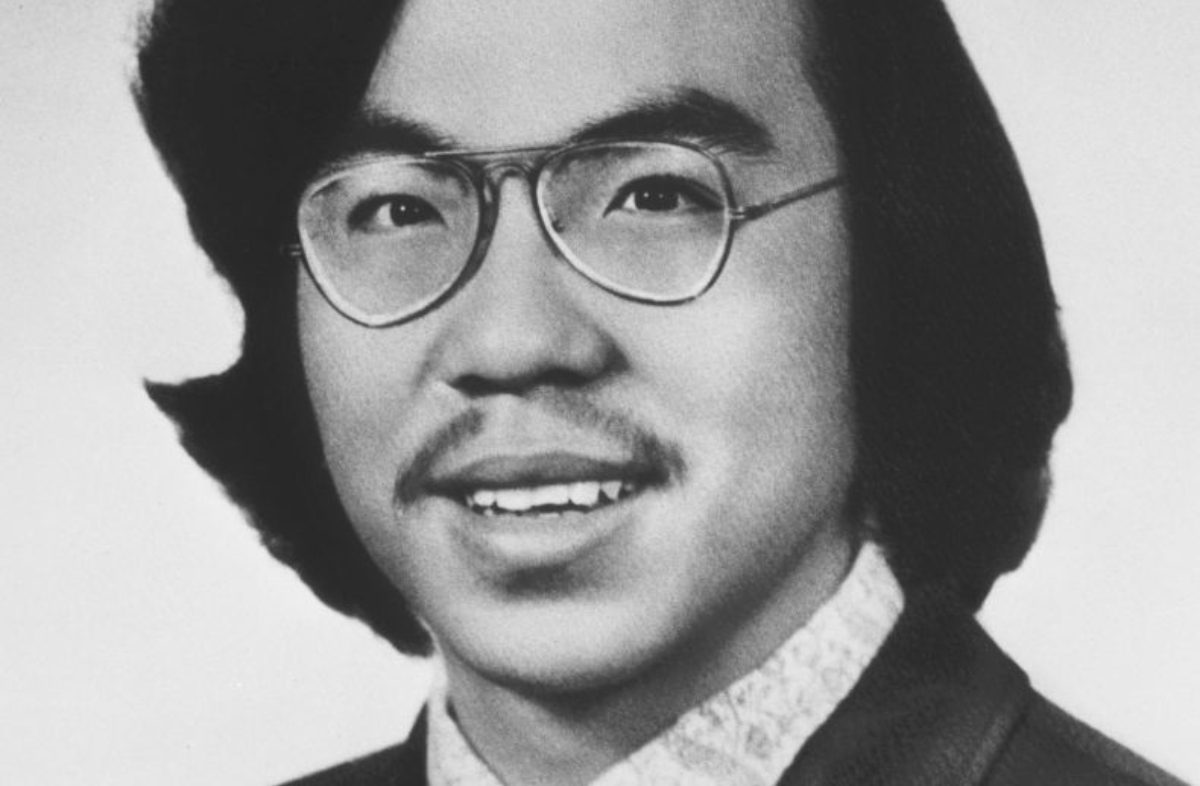

Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images.

In June 1982, 27-year-old Vincent Chin was attacked and killed in Detroit, Michigan. Chin, a Chinese-American, was the victim of a hate crime carried out by two men who mistakenly believed he was Japanese. The attackers, Ronald Ebens and Michael Nitz, both worked for Chrysler (though Nitz had recently lost his job there). They were angered by Detroit’s decline as the automotive manufacturing capital and blamed it on Japanese car manufacturers.

What happened to Chin, and the aftermath of the attack, is deeply embedded in Detroit history. When Kimberly Lawson, VP of the Community Department at Courier Newsroom (‘Gander’s parent company) suggested that I write about Vincent Chin for AAPI Heritage Month, I knew it was something I wanted to handle with care.

The more I researched what happened to him, the more I realized that I wanted to tell the full story. I didn’t want this to be another article that just detailed the specifics of the crime, or how his attackers were only initially given fines and probation instead of jail time for murder. I wanted this piece to be, first and foremost, about Chin: his life, the type of person he was, and his hopes for the future.

Vincent Chin’s early life

Vincent Chin was born on May 18, 1955 in China’s Guangdong province. In 1961, he was adopted by Bing Hing “David” Chin and Lily Chin, an American couple living in Michigan at the time. The family lived in the Highland Park neighborhood of Detroit until the early 1970s before eventually settling into Oak Park.

Details about Chin’s childhood in Detroit are scarce, though the image of who he was becomes sharper in his teenage years. The Vincent Chin Institute says he was known for being outgoing—he was “an avid reader, wrote poetry, and, like his parents, was involved with Detroit’s Chinese-American community centered in the Cass corridor, where Chinatown was then located.”

He graduated from Oak Park High School in 1973 and went on to study at the Control Data Institute (a technical vocational school). Following his time there, Chin went on to study at the Lawrence Technological University in Southfield, Michigan. At the time of his murder, he had been working at Efficient Engineering as an industrial draftsman.

As the only child of older parents, Chin spent much of his adult life caring for them financially. His father passed away in 1981, but Chin continued to provide for his mother. In addition to working as an industrial draftsman, he was a waiter at the Golden Star Restaurant in Ferndale. He was also attending night school for computer operations. Coworkers described him as being easy-going, friendly, and hard-working.

A family-oriented man, Chin became engaged to Victoria Wong in the early 1980s. They were set to be married on June 28, 1982. Chin would die five days before their wedding.

Vincent and Victoria

Vincent Chin and Victoria Wong met and fell in love in 1979 and became engaged a few years later. The pair were looking forward to buying a house (complete with a room for Vincent’s mother, Lily Chin), settling down, and starting a family.

The couple’s friends spoke with the Detroit Free Press in July 1982 about the wedding that never came to be. Wong’s friend and coworker, Leah Shafer, told the publication that Wong was planning on wearing two dresses: An American-style wedding gown for the ceremony and a traditional Chinese gown at the reception.

Paul Chin, a friend of Vincent’s, said the pair was going to honeymoon in Aruba. “He was really excited about that,” Paul told the publication. The honeymoon was set to coincide with Wong’s 24th birthday on July 2.

Wong has, understandably, chosen to protect her privacy in the 40-odd years since Vincent was killed. The last time she spoke about him publicly was in 1983, following the uproar surrounding Ronald Ebens’ lack of prison time for Vince’s murder. “This controversy just goes on, and I don’t want to say any more about it,” Wong said. She added, “It still hurts me very much.”

Author Paula Yoo reached out to Wong for comment when Yoo was working on her book, “From a Whisper to a Rallying Cry: The Killing of Vincent Chin and the Trial that Galvanized the Asian American Movement.” Wong declined to comment. However, her son, Jarod Lew, assisted Yoo with her book as a photographer.

When Yoo spoke with Lew about his mother’s decision to not discuss her relationship with Vincent, Lew said: “She was about to give an interview but decided not to. I asked her why, and her response was, ‘Jarod, I really would like to do this for you, but I really had a hard time sleeping last night and have so much anxiety that I don’t think I can do this. I’m sorry.’”

Lew understood. Speaking with Yoo, he said, “I felt this pain in her voice that was so searing that I haven’t been able to talk to her about it since. This made me confront how the Asian American experience cannot be expressed with words sometimes. We cannot always speak out because there are no words that can describe the abuse and erasure we have faced.”

Thinking about the past brought back feelings of anger and grief for Wong. Not only did she lose the man she loved to a violent crime, but she had to spend years afterward dealing with the public spotlight on her and Vincent’s family in the throes of their grief.

As Yoo states in her piece, “Grieving Vincent Chin, 39 Years Later,” Wong “had been engaged to the man who was at the heart of the first federal civil rights trial for an Asian American, The United States v. Ronald Ebens and Michael Nitz.”

Wong, for her part, eventually found a way to move forward from the tragedy. She got married and had two sons.

June 19-29, 1982

On the night of June 19, 1982, Vincent Chin was out celebrating his bachelor party. Chin, alongside a group of friends including Gary Koivu, Robert Siroskey, and Jimmy Choi, were at the Fancy Pants Club in Detroit when they encountered Ronald Ebens and his stepson, Michael Nitz.

The altercation came during a charged time in Detroit history. Massive layoffs were taking place across the automotive industry, and the city was in the midst of an economic recession. Reflecting on this period, the National Parks Service stated, “As people struggled financially, their desperation turned to anger. They looked for someone to blame.” Ebens and Nitz, for their part, decided to blame Chin—despite the fact that he was Chinese-American and didn’t even work in the auto industry.

According to Racine Colwell, a dancer at the club, Ebens and Nitz (who were both white) began shouting racially charged remarks at Chin, who they mistakenly believed was Japanese. Ebens and Nitz then got into a physical altercation with Chin inside the club. Following the brief fight, Chin and his friends left.

Ebens and Nitz claim that Chin’s friend, Siroskey, came back to apologize to them on Chin’s behalf. However, when the pair left the club, they ran into Chin and his friends, who were waiting outside for Siroskey to return. Ebens and Nitz then began to yell at Chin, and Nitz retrieved a baseball bat from his car. Chin then ran down the street with his friends in an attempt to avoid and deescalate the situation.

Instead of letting it go, Ebens and Nitz decided to search the surrounding neighborhood for close to 30 minutes to find Chin. They came across him at a nearby McDonald’s. Chin again attempted to flee, but was grabbed and held by Nitz while Ebens bludgeoned Chin, repeatedly, with the baseball bat. Two off-duty police officers witnessed the attack and ordered Ebens, at gunpoint, to drop the weapon. They arrested Ebens on site. Officer Michael Gardenhire also called for an ambulance. Chin was rushed to Henry Ford Hospital, but he was comatose when he arrived. Reports indicate that his skull was fractured during the attack.

Chin never regained consciousness. He subsequently died from his wounds four days later on June 23, 1982. His mother, Lily Chin, and his fiancée, Victoria Wong, were by his side when he passed.

His funeral was held on June 29, 1982, one day after his wedding was supposed to take place.

Aftermath of the attack

Lily Chin, mother of Vincent Chin, breaks down as a relative (L), helps her walk while leaving Detroit’s City County Building. Mrs. Chin. along with the American Citizens for Justice, asked Judge Charles Kaufman to resentence the two involved in the slayings. Kaufman sentenced the men to 3 years probation after plea bargaining agreements. (Photo by Bettmann/ Contributor for Getty Images).

Ronald Ebens and Michael Nitz were initially charged with second-degree murder for the death of Vincent Chin. They negotiated a plea bargain by confessing to a lesser charge of manslaughter. The men were ordered to serve three years of probation and to pay $3,000 in fines, plus an additional $780 in court fees. They were not given any jail time for the crime they carried out.

According to the “Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Society, Vol. 1,” witnesses were not asked to testify at the trial and neither was Vincent’s mother, Lily Chin. Wayne County circuit judge Charles Kaufman, a WWII veteran who was a prisoner of war in a Japanese prison camp, presided over the case. Speaking about his decision to not give Ebens and Nitz prison time, Kaufman was quoted as saying that the two “weren’t the kind of men you send to jail.”

Kaufman’s sentencing led to immediate and widespread outcry among Detroit’s Asian community and across the US. Several Asian civil rights groups and organizations formed a coalition, the American Citizens for Justice (ACJ), and, along with Lily, appealed the verdict. The ACJ—established by Kin Yee, James Shimoura, Helen Zia, Roland Hwang, and others—worked with Asian American and Pacific Islander communities across the country to raise money for their cause and bring awareness to the grave injustice taking place.

Eventually, they were able to persuade the FBI to investigate Vincent’s case. In November 1983, new charges were brought against Ebens and Nitz. They were accused of two counts of violating Vincent’s civil rights, and the federal case against them was heard in 1984. Ebens was found guilty of the second count of civil rights violations and was sentenced to 25 years in prison. Nitz was acquitted on both counts.

However, Ebens’ conviction was then overturned in 1986 after a federal appeals court stated that an ACJ attorney had coached witnesses improperly. He did not serve any jail time for Chin’s murder. A retrial subsequently took place in Cincinnati, where Ebens was tried by a predominantly white, male jury. He was acquitted on all charges.

Civil suits were then filed, and settled, in 1987. Nitz was ordered to pay $50,000 and Ebens was ordered to pay $1.5 million in the settlement. Nitz paid his settlement. Ebens did not. For additional information on Ebens’ lack of payment and how Vincent’s estate has repeatedly attempted to receive the settlement, click here to read more from The Detroit News.

Vincent Chin’s legacy

The attack on Vincent Chin, and the legal proceedings following his death, are both considered crucial turning points for civil rights engagement within the Asian American community. Though what happened to Chin is largely considered a hate crime, the United States did not have hate crime laws in place at the time of his attack.

Both local and nationwide civil rights advocacy groups and community members helped advocate for federal hate crime legislation that would protect Asian Americans in the future. The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 was eventually passed, ensuring that individuals could be charged with a hate crime under state and federal law.

In 2010, a marker was erected in Ferndale, Michigan to commemorate Chin’s life and to call attention to “the struggle for justice that followed.” More recently, in 2023, the Vincent Chin Institute was established to “come together to embrace our shared history and envision the future as communities united, to strengthen our fragile democracy and honor the legacy of Vincent Chin.”

Though there is still much improvement to be made to combat anti-Asian hate across the country, Helen Zia, the Executor of Vincent and Lily Chin’s estate, believes in the work being done at the Vincent Chin Institute.

Zia stated, “The Chin Estate, ACJ, and the Planning Committee believe that Vincent Chin’s legacy will continue to advance the ideals of equal justice; solidarity against racism and hate that Lily Chin courageously stood for; and respect for the individuals and communities who stood together for justice for Vincent Chin and who are standing up today for all communities to live without fear of violence.”

Michigan’s cult chronicles: A look at 5 controversial groups

Discover all the cults with solid ties to Michigan, from the Twin Flames Universe to the Church of Scientology. Society has long been fascinated by...

That one time in Michigan: When prisoners of war helped to fill a labor shortage

How thousands of POWs assisted in Michigan's agricultural sector during World War II. During World War II, 16 million US troops were sent overseas...

That one time in Michigan: When two sisters pioneered women’s higher education

The story of Michigan Female College. In the mid-1800s, Michigan was a young developing state that was working hard to establish an educational...

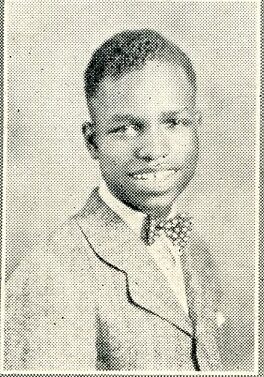

Charles A. Pratt’s legacy: How Kalamazoo County will honor its first African American judge

Learn about Hon. Charles A. Pratt, Kalamazoo County's first African American judge, and the upcoming ceremony to honor his trailblazing work. ...

What to know about Labor Day and its history

By JAMIE STENGLE Associated Press DALLAS (AP) — From barbecues to getaways to shopping the sales, many people across the U.S. mark Labor Day — the...